1.FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Data; www.faostat.fao.org (last access 15.06.21), (2016).2.Gomez, D., Salvador, P., Sanz, J. & Casanova, J. L. Modelling wheat yield with antecedent information, satellite and climate data using machine learning methods in Mexico. Agric. For. Meteorol. 300, 108317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.108317 (2021).ADS Article Google Scholar 3.Wrigley, C. W. Wheat: A unique grain for the world. In Wheat chemistry and technology 4th edn (eds Khan, K. & Shewry, P. R.) 1–17 (AACC Int. Inc, St Paul, 2009). Google Scholar 4.Awika, J. M. Major cereal grains production and use around the world. In Advances in Cereal Science: Implications to Food Processing and Health Promotion, Vol. 1089 (eds Awika, J. M., Piironen, V. & Bean, S.) 1–13 (American Chemical Society, 2011).5.Gupta, R., Meghwal, M. & Prabhakar, P. K. Bioactive compounds of pigmented wheat (Triticum aestivum): Potential benefits in human health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 110, 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.003 (2021).CAS Article Google Scholar 6.FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Data; www.faostat.fao.org (last access 15.06.21), (2020).7.USDA. Grain and Feed Annual. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), MO2020-0007; https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/morocco-grain-and-feed-annual-3 (last access 15.06.21), (2020).8.McIntyre, C. L. et al. Molecular detection of genomic regions associated with grain yield and yield-related components in an elite bread wheat cross evaluated under irrigated and rainfed conditions. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120, 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-009-1173-4 (2010).CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar 9.UN. World population prospects. United Nations (UN), Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA); https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2017.html (last access 15.06.21), (2017).10.Gomez-Macpherson, H. & Richards, R. A. Effect of sowing time on yield and agronomic characteristics of wheat in south-eastern Australia. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 46, 1381–1399. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9951381 (1995).Article Google Scholar 11.Stone, P. J. & Nicolas, M. E. Effect of timing of heat stress during grain filling on two wheat varieties differing in heat tolerance. I. Grain growth. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 22, 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1071/PP9950927 (1995).Article Google Scholar 12.Mahdi, L., Bell, C. J. & Ryan, J. Establishment and yield of wheat (Triticum turgidum L.) after early sowing at various depths in a semi-arid Mediterranean environment. Field Crops Res. 58, 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4290(98)00094-X (1998).Article Google Scholar 13.Radmehr, M., Ayeneh, G. A. & Mamghani, R. Responses of late, medium and early maturity bread wheat genotypes to different sowing date. I. Effect of sowing date on phonological, morphological, and grain yield of four breed wheat genotypes. Iran. J. Seed. Sapling 21, 175–189 (2003). Google Scholar 14.Turner, N. C. Agronomic options for improving rainfall use efficiency of crops in dryland farming systems. J. Exp. Bot. 55, 2413–2425. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erh154 (2004).CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar 15.Pickering, P. A. & Bhave, M. Comprehensive analysis of Australian hard wheat cultivars shows limited puroindoline allele diversity. Plant Sci. 172, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.09.013 (2007).CAS Article Google Scholar 16.Zheng, B., Chenu, K., Fernanda Dreccer, M. & Chapman, S. C. Breeding for the future: What are the potential impacts of future frost and heat events on sowing and flowering time requirements for Australian bread wheat (Triticum aestivium) varieties?. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 2899–2914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02724.x (2012).ADS Article Google Scholar 17.Wu, X. S., Chang, X. P. & Jing, R. L. Genetic insight into yield-associated traits of wheat grown in multiple rain-fed environments. PLoS ONE 7, e31249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031249 (2012).ADS CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 18.Mueller, B. et al. Lengthening of the growing season in wheat and maize producing regions. Weather Clim. Extrem. 9, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2015.04.001 (2015).Article Google Scholar 19.Hunt, J. R., Hayman, P. T., Richards, R. A. & Passioura, J. B. Opportunities to reduce heat damage in rainfed wheat crops based on plant breeding and agronomic management. Field Crops Res. 224, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2018.05.012 (2018).Article Google Scholar 20.Ababaei, B. & Chenu, K. Heat shocks increasingly impede grain filling but have little effect on grain setting across the Australian wheatbelt. Agric. For. Meteorol. 284, 107889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.107889 (2020).ADS Article Google Scholar 21.Anderson, W. K. & Smith, W. R. Yield advantage of two semi-dwarf compared with two tall wheats depends on sowing time. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 41, 811–826. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9900811 (1990).Article Google Scholar 22.Connor, D. J., Theiveyanathan, S. & Rimmington, G. M. Development, growth, water-use and yield of a spring and a winter wheat in response to time of sowing. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 43, 493–516. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR9920493 (1992).Article Google Scholar 23.Owiss, T., Pala, M. & Ryan, J. Management alternatives for improved durum wheat production under supplemental irrigation in Syria. Eur. J. Agron. 11, 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1161-0301(99)00036-2 (1999).Article Google Scholar 24.Bassu, S., Asseng, A., Motzo, R. & Giunta, F. Optimizing sowing date of durum wheat in a variable Mediterranean environment. Field Crops Res. 111, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2008.11.002 (2009).Article Google Scholar 25.Bannayan, M., Eyshi Rezaei, E. & Hoogenboom, G. Determining optimum sowing dates for rainfed wheat using the precipitation uncertainty model and adjusted crop evapotranspiration. Agric. Water Manag. 126, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2013.05.001 (2013).Article Google Scholar 26.Liang, Y. F. et al. Subsoiling and sowing time influence soil water content, nitrogen translocation and yield of dryland winter wheat. Agronomy 9, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9010037 (2019).Article Google Scholar 27.Farooq, M., Basra, S. M. A., Rehman, H. & Saleem, B. A. Seed priming enhances the performance of late sown wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) by improving chilling tolerance. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 194, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.2007.00287.x (2008).Article Google Scholar 28.Kudair, I. M. & Adary, A. H. The effects of temperature and planting depth on coleoptile length of some Iraqi local and introduced wheat cultivars. Mesopotamia J. Agric. 17, 49–62 (1982). Google Scholar 29.Leoncini, E. et al. Phytochemical profile and nutraceutical value of old and modern common wheat cultivars. PLoS ONE 7, e45997. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0045997 (2012).ADS CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 30.Busko, M. et al. The effect of Fusarium inoculation and fungicide application on concentrations of flavonoids (apigenin, kaempferol, luteolin, naringenin, quercetin, rutin, vitexin) in winter wheat cultivars. Am. J. Plant Sci. 5, 3727–3736. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajps.2014.525389 (2014).CAS Article Google Scholar 31.Bannayan, M., Kobayashi, K., Marashi, H. & Hoogenboom, G. Gene-based modeling for rice: An opportunity to enhance the simulation of rice growth and development?. J. Theor. Biol. 249, 593–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.08.022 (2007).ADS CAS Article PubMed MATH Google Scholar 32.Soler, C. M. T., Sentelhas, P. C. & Hoogenboom, G. Application of the CSM-CERES-Maize model for sowing date evaluation and yield forecasting for maize grown off-season in a subtropical environment. Eur. J. Agron. 18, 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2007.03.002 (2007).Article Google Scholar 33.Andarzian, B. et al. WheatPot: A simple model for spring wheat yield potential using monthly weather data. Biosyst. Eng. 99, 487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2007.12.008 (2008).Article Google Scholar 34.Andarzian, B., Hoogenboom, G., Bannayan, M., Shirali, M. & Andarzian, B. Determining optimum sowing date of wheat using CSM-CERES-Wheat model. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 14, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2014.04.004 (2015).Article Google Scholar 35.Palosuo, T. et al. Simulation of winter wheat yield and its variability in different climates of Europe: A comparison of eight crop growth models. Eur. J. Agron. 35, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2011.05.001 (2011).Article Google Scholar 36.Rötter, R. P. et al. Simulation of spring barley yield in different climatic zones of Northern and Central Europe: A comparison of nine crop models. Field Crops Res. 133, 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.03.016 (2012).Article Google Scholar 37.Ran, H. et al. Capability of a solar energy-driven crop model for simulating water consumption and yield of maize and its comparison with a water-driven crop model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 287, 107955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.107955 (2020).ADS Article Google Scholar 38.Keating, B. A. et al. An overview of APSIM, a model designed for farming systems simulation. Eur. J. Agron. 18, 267–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1161-0301(02)00108-9 (2003).Article Google Scholar 39.Probert, M. E. & Dimes, J. P. Modelling release of nutrients from organic resources using APSIM. In Modelling nutrient management in tropical cropping systems Vol. 114 (eds Delve, R. J. & Probert, M. E.) 25–31 (ACIAR Proceedings, 2004).40.Mohanty, M. et al. Simulating soybean–wheat cropping system: APSIM model parameterization and validation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 152, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.02.013 (2012).Article Google Scholar 41.George, N., Thompson, S. E., Hollingsworth, J., Orloff, S. & Kaffka, S. Measurement and simulation of water-use by canola and camelina under cool-season conditions in California. Agric. Water Manag. 196, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2017.09.015 (2018).Article Google Scholar 42.Bahri, H., Annabi, M., M’Hamed, H. C. & Frija, A. Assessing the long-term impact of conservation agriculture on wheat-based systems in Tunisia using APSIM simulations under a climate change context. Sci. Total Environ. 692, 1223–1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.307 (2019).ADS CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar 43.Ahmed, M. et al. Novel multimodel ensemble approach to evaluate the sole effect of elevated CO2 on winter wheat productivity. Sci. Rep. 9, 7813. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44251-x (2019).ADS CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 44.Eyni-Nargeseh, H., Deihimfard, R., Rahimi-Moghaddam, R. & Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A. Analysis of growth functions that can increase irrigated wheat yield under climate change. Meteorol. Appl. 27, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/met.1804 (2020).Article Google Scholar 45.Rahimi-Moghaddam, S., Eyni-Nargeseh, H., Kalantar Ahmadi, S. A. & Azizi, K. Towards withholding irrigation regimes and resistant genotypes as strategies to increase canola production in drought-prone environments: A modeling approach. Agric. Water Manag. 243, 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106487 (2021).Article Google Scholar 46.Berghuijs, H. N. C. et al. Calibrating and testing APSIM for wheat-faba bean pure cultures and intercrops across Europe. Field Crops Res. 264, 108088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108088 (2021).Article Google Scholar 47.METLE. National Report. Ministry of Equipment, Transport, Logistics and Water (last access 15.06.21), (2019).48.HCP. Voluntary national review of the implementation of the sustainable development goals. High Comm. Plng. p. 188 (2020).49.Hammer, G. L. et al. Adapting APSIM to model the physiology and genetics of complex adaptive traits in field crops. J. Exp. Bot. 61, 2185–2202. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erq095 (2010).CAS Article PubMed Google Scholar 50.Holzworth, D. P. et al. APSIM—evolution towards a new generation of agricultural systems simulation. Environ. Model. Softw. 62, 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.07.009 (2014).Article Google Scholar 51.Gaydon, D. S. et al. Evaluation of the APSIM model in cropping systems of Asia. Field Crops Res. 204, 52–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2016.12.015 (2017).Article Google Scholar 52.Climate Kelpie website. http://www.climatekelpie.com.au/manage-climate/decision-support-tools-for-managing-climate (2010).53.McCown, R. L., Hammer, G. L., Hargreaves, J. N. G., Holzworth, D. P. & Freebairn, D. M. APSIM: A novel software system for model development, model testing and simulation in agricultural systems research. Agric. Syst. 50, 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/0308-521X(94)00055-V (1996).Article Google Scholar 54.Cichota, R., Vogeler, I., Werner, A., Wigley, K. & Paton, B. Performance of a fertiliser management algorithm to balance yield and nitrogen losses in dairy systems. Agric. Syst. 162, 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2018.01.017 (2018).Article Google Scholar 55.Laurenson, S., Cichota, R., Reese, P. & Breneger, S. Irrigation runoff from a rolling landscape with slowly permeable subsoils in New Zealand. Irrig. Sci. 36, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00271-018-0570-3 (2018).Article Google Scholar 56.Rodriguez, D. et al. Predicting optimum crop designs using crop models and seasonal climate forecasts. Sci. Rep. 8, 2231. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20628-2 (2018).ADS CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 57.Archontoulis, S. V., Miguez, F. E. & Moore, K. J. A methodology and an optimization tool to calibrate phenology of short-day species included in the APSIM PLANT model: Application to soy

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02668-3

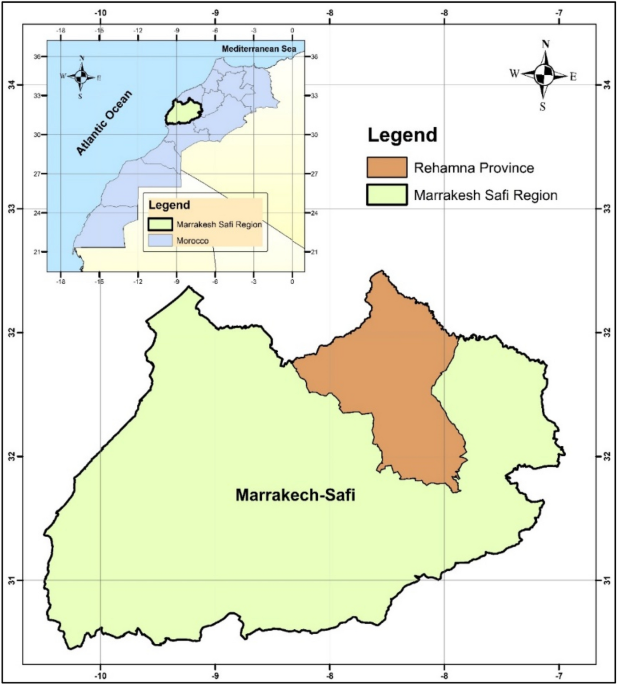

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) adaptability evaluation in a semi-arid region of Central Morocco using APSIM model