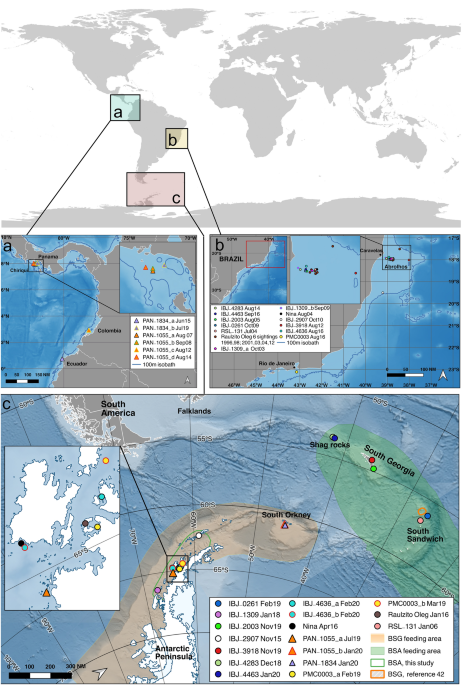

We found new evidence of summer co-occurrence of two recovering humpback whale breeding populations from the Atlantic (Brazil, BSA) and Pacific (Central and South America, BSG) in the West Antarctic Peninsula feeding area. The temporal pattern of resightings of BSA individuals (older sightings in South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands and more recent sightings off the WAP) suggests BSA whales may be making more extended feeding area movements in recent years. Photo-identifications collected from South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (Table 1) add to the previous evidence that this area is a known feeding area for whales belonging to BSA. For example, the oldest record of an individual photo-identified at Abrolhos Bank, Brazil in 1989 and matched to its feeding area was for whale IBJ-0261 (Table 1). This individual was photo-identified almost 30 years later in the South Sandwich Islands in 2019, the feeding area for BSA. Photo-identifications available in Happywhale from the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands mostly come from recent efforts and presently include only 322 identified individuals, 7% of the WAP sample size, thus this effort offers a limited sighting history for photo-identification matching, perhaps explaining the lower number of matches compared to the matches seen between the WAP and wintering grounds in Pacific Central and South America.

Available photo-identification data from the South Orkney Islands is also limited in the Happywhale dataset, but of 17 individually identified humpback whales, two individuals (PAN-1055 and PAN-1834) have been resighted on BSG breeding areas off Ecuador, Colombia, and Panama (Table 1, Figs. 1, 2). Notably, individual PAN-1055 may have migrated north late (or not at all) during the 2019 winter providing information on recent unusual movements around southern polar waters. The breeding destination of the other 15 identified whales in the South Orkney Islands remains to be determined.

Despite differences in photo-identification effort among breeding areas, this study reveals the first evidence of whales moving from Brazil into BSG feeding areas, reinforcing the proposed ‘Southern Ocean Exchange’. As such, the WAP feeding area is used by two different breeding stocks, BSG and BSA, which were previously strongly differentiated, and now co-occur in polar waters. Increasing photo-identification efforts in this region should provide further evidence of this assessment. The number of individuals that migrate between these two breeding stocks has been estimated to be 1–1.5 whales per season33. Two BSA individuals (named Nina and Raulzito Oleg) were photo-identified off the WAP, crossing the boundary between feeding areas attributed to BSA and BSG in the same period (January 2016, austral summer) and relatively close together (Fig. 1c). This is strong evidence that at least in recent years the use of BSG feeding areas by BSA whales is not a rare event.

While humpback whales are nearly global in their distribution, there is strong evidence that the equator represents a barrier to movement of this species9,49. Mitochondrial and nuclear genetic differentiation is stronger among humpback whales from different hemispheres (North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Hemisphere) than among humpback whales from three Southern Hemisphere ocean basins (Indian, South Pacific, and South Atlantic), suggesting that gene flow is greater across the Southern Hemisphere oceans than across the equator9,50. This has led to a proposal to separate humpback whales into North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Hemisphere subspecies9,50. Levels of genetic differentiation are weaker among Southern Hemisphere breeding stocks12,13 but sufficiently strong that they have been considered demographically independent populations, with population assessments of recovery from exploitation carried out at the level of each breeding stock51. Within the Southern Hemisphere, inter-population genetic differentiation may be anticipated to decrease, as populations recover from whaling and migratory movements between populations increase. If the crossing of individuals from BSA into BSG feeding areas is a recent event, likely motivated by population recovery, the observations presented in this study support this hypothesis.

Mixing of Southern Hemisphere humpback whales on high latitude feeding areas (the Southern Ocean Exchange), sometimes leading to movements between breeding stocks, might be influenced by geographic features such as landmasses, and oceanographic barriers such as major ocean currents that restrict movements. Additionally, El Niño and La Niña climatic events influence the distribution of prey and therefore may potentially influence the migratory destination and timing of migration41. The observed long-range movements between Southern Hemisphere oceans may also result from increasing population size52 and expanding distribution range, as whales colonize new areas and reoccupy historical breeding and feeding areas5,53,54.

Unique features that determine oceanographic and ecological characteristics of the Southern Ocean, such as climate and sea-ice extent variability that affect krill productivity and distribution dynamics, can also influence individual decision-making about migratory paths to these feeding destinations55. Observed shifts in migration timing of humpback whales from Antarctic feeding areas to earlier arrival at breeding areas in the Eastern Tropical Pacific off Colombia are also believed to be associated with population growth (e.g., high pregnancy rates detected in WAP56) and reductions in sea ice coverage and pack mass during the austral autumn, which, in turn, should influence krill availability in Antarctica57. When the autumn ice sheet has a larger mass, more krill can find food in winter58,59 and during the following summer, there are more prey available for whales. In years with larger autumn ice sheets, humpback whales arrive later to Colombian waters the following winter. Prey availability is probably used by whales as a cue to time their migration to wintering areas57.

Krill availability along the WAP correlates with reproductive rates in BSG whales, suggesting the importance of krill to the dynamics of this population60. Although krill abundance in the southwest Atlantic sector is one of the largest in the Southern Ocean, krill density in South Georgia is declining61,62 and show interannual fluctuation linked to climate variability63, with population-level impacts on other krill predators using South Georgia waters64. High krill density values (> 30 g m−2) are interspersed with years with low density (< 30 g m−2) with fluctuations every 4–5 years65. The relationship between BSA whale population growth (12% per year66) and krill availability is yet to be established but is assumed to be similar to that found for BSG. Increasing fluctuations in krill availability in the northern Scotia Arc may also be forcing humpback whales to venture further from their traditional feeding areas in order to feed. Melting sea ice around the WAP may open up new habitats and modulate krill densities and distributions across the Peninsula and into the Scotia Arc67 which, in turn, may have a dampening effect on whale population growth while increasing the likelihood that humpback whales from different populations will venture into areas that were not traditionally utilized for feeding in that part of the ocean.

Behavioural traits such as humpback whale song and its evolution and transmission are also facilitated by the Southern Ocean Exchange. In humpback whales, songs are produced by males68,69. Molecular data also suggests most movements between breeding grounds, and associated gene flow, may be male-driven33. Male carriers of a particular song may therefore introduce it to another population. Cultural transmission of song patterns by males has been shown to occur between west and east coasts of Australia70 and across the South Pacific Ocean15. The lower site fidelity of males therefore facilitates song sharing among breeding grounds in the Southern Hemisphere16,71. The co-occurrence of whales from different populations could also contribute to the spread of infectious diseases. In seabird populations, extensive winter mixing has been suggested as an important factor in disease transmission72. For example, morbillivirus was recently identified in the blow of humpback whales in Brazil73 and it could be introduced to other breeding areas through whales that migrate away from their natal breeding and feeding grounds.

Here we have considered how population growth, climate change and oceanic productivity may be acting synergistically to increase the porosity of boundaries among feeding areas of different humpback whale breeding stocks. Underscoring the Southern Ocean Exchange hypothesis of porous Southern Ocean boundaries for humpbacks are the international collaborations among academics and citizens which have made these observations possible. Traditionally, fluke comparisons between regions were very time-consuming as they were carried out manually by researchers visually inspecting all images74. New algorithms and tools for automated fluke matching, such as the one developed and implemented by Happywhale43 have enormously improved matching rates and also facilitate the detection of low-frequency movements. Photo-identification sample sizes used in humpback whale stock comparisons jumped 50-fold when citizens started to participate in biodiversity monitoring, facilitated by public campaigns, tourism, and the development of user-friendly platforms to engage and receive feedback on their contributions. In ours and other cases, these contributions add great complementary value to dedicated scientific research75,76. Global citizen engagement informs, at a much faster pace, stakeholders’ actions towards conservation of marine life. The relative cost of citizen science compared to more academic approaches in wildlife monitoring may change how conservation science is made and perceived by society in the near future.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02612-5