Spatiotemporal characteristic of Biantun toponymical landscape for the evolution of Biantun culture in Yunnan, China The geographical environment of Yunnan Province in China and Han migration during the Ming Dynasty contributed to the development of the Biantun culture. Biantun toponyms (BTT) record the integration process between the Central Plains and native Yunnan cultures. The GIS analysis method of toponyms was used in this study to reproduce the settlement characteristics of BTT and the spatial development of the Biantun culture in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. In addition, we have developed a toponymical landscape index to represent the degree of spatial integration between the BTT and ethnic minority toponyms in Yunnan and explore the spatial characteristics of the integration of Han immigrants and local ethnic minorities. The results show that the spatial distribution of the BTT is consistent with the sites selection of the Tuntian (屯田) in Yunnan during the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and the centroids of BTT spread to outskirts and intermontane area from central towns. In the Dali, Kunming, Qujing and other regions, the distribution characteristics of the integrated of BTT and ethnic minority toponyms reflect a higher degree of Sinicization in the central urban areas. Exploring the evolution of Biantun cultural development through the spatial characteristics of toponymical landscapes can help adjust policies for the development and protection of Biantun cultural resources. The ‘Tun (屯)’ in the Biantun culture originally means cluster, and ‘Biantun (边屯)’ refers to established settlements (clusters) in frontier regions. Specifically, Biantun culture refers to a comprehensive cultural phenomenon that occurred during the historical process of developing, building, and defending the frontier by the ethnic groups who migrated and settled in those frontiers, as well as their native residents. Biantun culture takes the Central Plains culture as the core, relies on the frontier regional culture, integrating the traditional culture of the local ethnic groups, with the typical cultural characteristics of garrison reclamation to guard the frontier1.Yunnan is a large province in the frontier and has been an important region for ethnic migration and cultural exchanges since ancient times. During the Hongwu (洪武) period of the Ming Dynasty, after stabilizing the situation in Yunnan, the Ming government established the WeiSuo (卫所)2,3,4 system and local institutions at different levels, carried out reclamation by garrisoning Yunnan. In order to meet the needs of military defense and facilitate the conditions for farming, the military WeiSuo were mainly stationed at important military places and basin districts, distributed along major traffic roads and around cities and towns5. Due to the development of the military Tun, civilian Tun and commercial Tun, a large number of Han immigrants from the Central Plains came to Yunnan and gradually integrated with the local ethnic groups through processes such as intermarriage. With the resulting changes in population structure, ethnic distribution, production relations, political systems, and cultural orientation, the Biantun culture of Yunnan flourished during this period1. There are still a large number of Biantun relics in Yunnan, such as toponyms such as Suo (所), Ying (营), Tun (屯), Pu (铺), etc. and guild halls. The protection of Biantun culture in Yunnan Province—including Yongsheng County, the site of Lancang Wei (卫), Mao’s Ancestral Hall, and Taliu (他留) culture6,7—provides rich resources for modern researchers.A cultural landscape is an area shaped by historical human activities, which possesses or retain special cultural value8. As an important part of a cultural landscape, toponyms are a powerful source of information. Toponyms can preserve information about social, linguistic, and political changes; production economy; military activities; and more9,10. As such, toponyms can provide information on the ways in which communities of historical settlers perceived and transformed their environments.Since 1990, quantitative research has gradually become the mainstream research method of place names. Computer technology has been introduced to optimize traditional research methods, promote the research of place names and cultural landscapes, and accumulate rich research results, such as national toponyms, plant toponyms and so on11,12,13,14,15,16. In addition, Siwei Qian et al.17 used spatial analysis methods to study the relationship between the spatial pattern of toponyms, ethnic population and topographical factors. Franco Capra et al.18 integrated an ethnopedological approach and mathematical statistics to study Sardinian toponyms influenced by natural and social factors. In summary, the main characteristics of quantitative research on toponyms is to combine traditional cultural geography research ideas, using GIS technology, computer technology and quantitative analysis methods to analyze toponym landscapes9.In this paper, we will analyze the evolution of Biantun culture from the perspective of BTT. The research on the BTT has so far been limited to the review of cultural connotations and historical evolution1,19,20. Most studies focused on Yongsheng County7,21 and lacked quantitative analysis. From the perspective of historical geography, we use GIS to quantitatively analyze the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics and historical evolution of the cultural landscape of BTT in Yunnan to reveal the relationship between spatial patterns of toponyms and the populations at different periods. The methods used in this study allow exploration of the geographical and spatial patterns of ethnic integration, which may introduce a new perspective on the emergence of Biantun culture.Yunnan is located on the southwestern border of China (Fig. 1). During the early Ming Dynasty (AD1368-1435), wars in Yunnan were frequent, and living conditions were extremely unstable. During the Hongwu years (AD1368–1398), military immigration of Han ethnic migrants occurred on a large scale22. During Yunnan unification and while consolidating the southwest frontier, the institutionalization of land reclamation and crop farming by stationed troops resulted in the mass migration of Han people to Yunnan. Most of the military migrants were concentrated in central towns and Tuntian (屯田) districts, where garrison troops and cultivating grassland/forestland were concentrated in the suburbs of important towns23.Figure 1Location of Yunnan and important sites of WeiSuo military institution in the Ming Dynasty. The map was created in ArcGIS Pro v.2.7: https://www.esri.com (Esri, California, USA). The final layout was created in ArcGIS Pro v.2.7: https://www.esri.com (Esri, California, USA).According to the Ming Dynasty system, Ying was the basic unit of the army, and Tun was an army resettlement system managed by the metropolis23. In the middle Ming Dynasty, conditions in Yunnan began to stabilize. Initially, Han immigrants began settling large-scale settlements on the outskirts of towns, followed by remote areas of flat land. The main Tuntian sites of the middle Ming Dynasty were named based on military units, including Wei, Suo, Qianhu, and Baihu, where the grade hierarchy was Wei (卫) > Suo (所) > Qianhu (千户) > Baihu (百户) 24. According to an order from Zhu Yuanzhang (the Ming emperor), the armies of WeiSuo had to be self-sufficient; this required one-seventh of the army to farm and one-third to guard the city22. Military yards around the Wei and Suo provided an economic source. Furthermore, the military yards of Yunnan reflected the emergence of toponyms during the middle Ming Dynasty (AD1436–1582), and were named after senior military chiefs’ surnames and suffixed with lower-level transportation trunk facilities and organization; for example, Yi (驿), Bao (堡), Pu (铺), Shao (哨), and others25,26.From the middle to the end of Ming Danasty, along with the development of immigrant agriculture, military yards moved to city outskirts, intermontane basins, and to semi-mountain areas. The original large-scale military yards were not suitable for agricultural development and production under the new terrain, which prompted the original basic organization of the Tuntian to shrink, and small organizational units such as Qi (旗), Wu (武), and Guan to appear. The toponyms that appeared at this time included the surname of the chief of the Qi (旗), Guan (官), and Wu (武), and the lower-level organizational units27.By the end of the Ming and early Qing dynasties (AD1583–1644), conditions in Yunnan were more stable; the population continued to increase and the branches of large clans began to spread. At this time, military-based toponyms faded, and some toponyms added the word ‘ Cun’ (村) after the words used in the original military units. In addition, they followed the floating official system of the Ming Dynasty and the upsurge in commerce, resulting in a large number of settlements wherein the Han nationality merged5.Through the integration of relevant historical materials and documents, thirteen types of place names (Ying (营), Tun (屯), Wei (卫), Suo (所), Baihu (百户), Qianhu (千户), Qi (旗), Guan (官), Wu (武), Yi (驿), Pu (铺), Bao (堡), and Shao (哨)) were selected in this study, with the Ming and Qing dynasties as the research time node. Based on the BTT screening procedure 28,29,30,31,32,33, 1112 toponyms in Yunnan Province were extracted.The second national toponymic census in China obtained the attribute content of place name origin (placeOrigi) and meaning (placeMeani), historical evolution (placeHisto), geographical entity overview and other attributes through data collation and field investigation. The meanings of toponyms indicate their natural, social, humanistic and economic significance. The historical evolution describes the changes in the creation and modification of toponyms. The information regarding Yunnan rural settlements, urban settlements, and mountain names was obtained from the National Database for Geographical Names of China (http://dmfw.mca.gov.cn/), as presented in Table 1.Table 1 Toponym information of second national toponymic census in China.Owing to changes in place names, current place names may not be identified by the aforementioned key words. Therefore, the following steps were used to determine whether the place name was a BTT. (1) Identification of place name attributes. Natural language processing integrates disciplines such as cognitive science, linguistics, and computer science to solve problems such as information retrieval, information extraction, and automatic abstraction. As a basic natural language processing technique, Chinese word segmentation recombines consecutive word sequences into word sequences according to certain specifications and performs preliminary attribute processing for screening of BTT 34,35. The villages and urban settlements where the stationed troops and military facilities were located during the Ming and Qing Dynasties were judged as BTT and were extracted using keywords such as ‘garrison’, ‘station troops’, and ‘set up sentry post’. The creation date of each toponym was extracted from the historical evolution field. If there is no exact year of the toponym in the field, the Tuntian date is extracted from the two fields of place name meaning and historical evolution. (2) Search historical documents If the creation date of toponym and Tuntian date are not known, gazetteers and related documents are checked and the time corresponding to the date of the local historical military immigrants is adopted. Research methodsSpatiotemporal analysis and visualization in GISMapping the toponyms directly is of limited value; spatial analysis techniques utilizing GIS can readily represent the characteristics of the spatio/temporal distributions of the toponyms, and analyze the effects of military WeiSuo on the development of BTT. Based on the clustering characteristics, the spatial model of the BTT distribution in different periods can be studied using the density characteristics of its points. In this study, the kernel density estimation (KDE) method was used to map the spatial clustering characteristics of all BTT and the small spatial scales of BTT in different periods. KDE is used to calculate the unit density of the point and line elements in a special neighborhood; this method provides the weighted average density of all points in the study area. The principle of KDE is to assign weights according to the distance between a data point and the center point, and the weight increases as the distance from the center point decreases36.Considering the complicated terrain of Yunnan, we selected a mountain range with large undulations to calculate the average distance between each pair, and finally selected bandwidths of 20 km, 30 km, and 40 km for comparison (Fig. 2) to determine the optimal bandwidth and analyze the distribution characteristics of BTT. It can be observed from the figure that the maximum density value with a bandwidth of 20 km is 0.078, the maximum density value with a bandwidth of 30 km is 0.043, and the maximum density value with a bandwidth of 40 km is 0.034. In KDE, the smaller the bandwidth, the greater is the density value within the bandwidth, and more irregular the distribution of density values; the larger the bandwidth, the smaller is the density value within the bandwidth and the smoother is the density value gradient. With 30 km as the bandwidth, it can clearly identify the density center of BTT and reflect the degree difference of the kernel density of the toponym.Figure 2Kernel density of BTT with bandwidth of 20 km, 30 km, 40 km. Maps were created in ArcGIS Pro v.2.7: https://www.esri.com (Esri, California, USA). The final layout was created in ArcGIS Pro v

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-03271-2

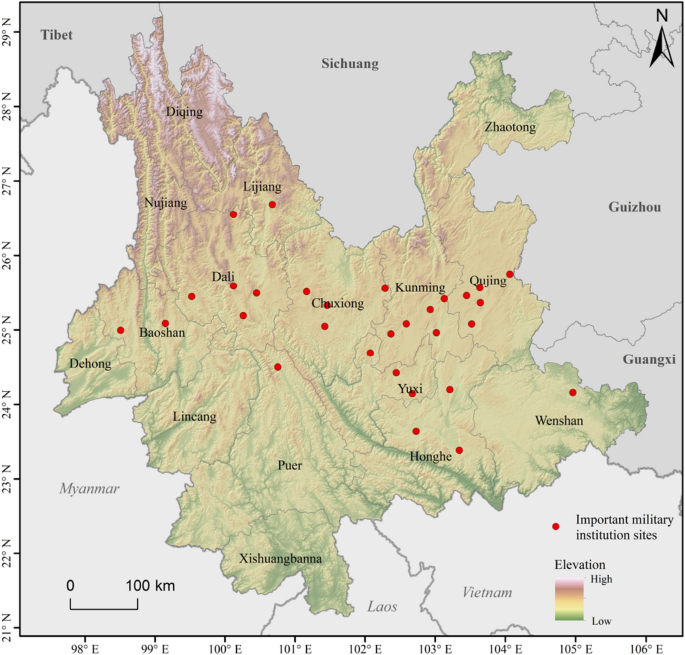

Spatiotemporal characteristic of Biantun toponymical landscape for the evolution of Biantun culture in Yunnan, China