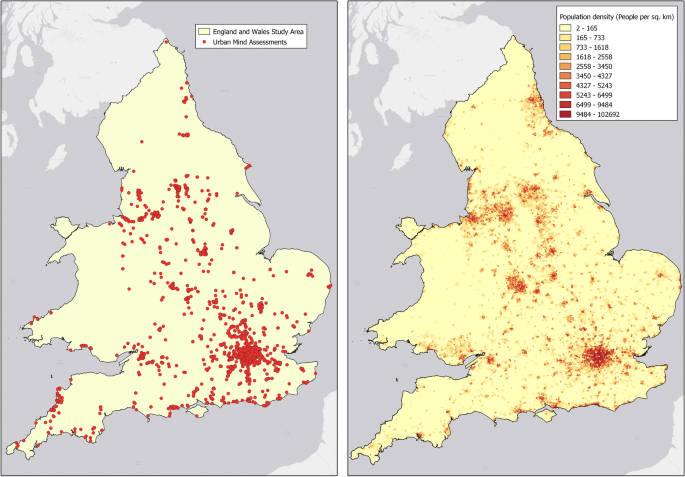

Lonely in a crowd: investigating the association between overcrowding and loneliness using smartphone technologies Ryan Hammoud1 na1, Stefania Tognin1,2 na1, Ioannis Bakolis3,4, Daniela Ivanova1, Naomi Fitzpatrick1, Lucie Burgess1, Michael Smythe5, Johanna Gibbons6, Neil Davidson6 & Andrea Mechelli1 Scientific Reports 11, Article number: 24134 (2021) Cite this article Loneliness is a major public health concern with links to social and environmental factors. Previous studies have typically investigated loneliness as a stable emotional state using retrospective cross-sectional designs. Yet people experience different levels of loneliness throughout the day depending on their surrounding environment. In the present study, we investigated the associations between loneliness and social and environmental factors (i.e. overcrowding, population density, social inclusivity and contact with nature) in real-time. Ecological momentary assessment data was collected from participants using the Urban Mind smartphone application. Data from 756 participants who completed 16,602 assessments between April 2018 and March 2020 were used in order to investigate associations between momentary feeling of loneliness, the social environment (i.e. overcrowding, social inclusivity, population density) and the built environment (i.e. contact with nature) using multilevel modelling. Increased overcrowding and population density were associated with higher levels of loneliness; in contrast, social inclusivity and contact with nature were associated with lower levels of loneliness. These associations remained significant after adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity, education and occupation. The positive association between social inclusivity and lower levels of loneliness was more pronounced when participants were in contact with nature, indicating an interaction between the social and built environment on loneliness. The feeling of loneliness changes in relation to both social and environmental factors. Our findings have potential implications for public health strategies and interventions aimed at reducing the burden of loneliness on society. Specific measures, which would increase social inclusion and contact with nature while reducing overcrowding, should be implemented, especially in densely populated cities. Despite the ever increasing levels of social connectivity, loneliness as a form of ‘social pain’ has become one of the defining issues of the modern society. Loneliness, defined as the ‘perceived sense of disconnection from others’, refers to the subjective emotional experience of not having one’s social need for relationships adequately met1. While initial research on loneliness focused on elderly populations2 or specific groups (e.g. childless, people with mental health issues)3,4, a recent study demonstrated that loneliness affects a much larger proportion of the society, with adults under 25 and above 65 feeling the loneliest5. Studies conducted in different countries tend to report similar loneliness rates with 1 in 10 adults feeling lonely5,6,7.Loneliness can be a normative and adaptive experience, for instance in response to bereavement, however, it can also have profound detrimental effects on mental and physical health3,8,9,10. For example, the degree of loneliness predicts subsequent mental health symptoms, including depression, alcoholism, suicidal behaviour and cognitive decline leading to dementia, and physical health issues, including immune and cardiovascular disease11,12. It is therefore unsurprising that due to the reported incidence rates combined with these detrimental effects on health, loneliness is increasingly recognised as a major public health concern within the scientific community4,8 and amongst the general media13.The term ‘loneliness’ is often associated with reduced social presence and social isolation14. However, mere social presence is not always linked with positive feelings, and loneliness and perceived social isolation have been found to be associated with, but distinct from, objective social isolation8. Perceived overcrowding tends to drive feelings of disconnectedness15. For example, Levine16,17 reported that when people are in highly populated areas they may feel that they do not have enough personal space, experience a higher level of social isolation and be less likely to help others in need. Chu et al.18 also showed how overcrowding might increase feelings of vulnerability, aggression and isolation. As the global population increases and more people move to large cities, with around 70% of the global population expected to live in urban areas by 205019, it becomes critical to understand how overcrowding affects our experience of loneliness.Related to overcrowding and at the other end of the disconnectedness-connectedness spectrum is the concept of social cohesion, which entails the interaction between the individual, the environment and the wider society20. A number of studies have implicated that social cohesion contributes to a sense of belonging within a community (i.e. social inclusion), which in turn promotes behaviours that have a positive effect on mental health, especially in time of distress21,22. Therefore, the feeling of social inclusivity within a particular sector of society might lessen the feeling of loneliness.In addition to social aspects such as overcrowding and social inclusivity, the experience of loneliness is thought to be influenced by features of the built environment. In particular, studies have suggested that green and blue spaces provide opportunities for socialising outdoor which in turn increases the sense of community belonging and social cohesion15,23,24,25. Other studies have suggested that, while green and blue spaces might not necessarily facilitate the creation or maintenance of social contact per se, they might promote general psychological wellbeing including greater sense of trust, acceptance and belonging26,27. Indeed, further research into the ‘sense of place’ and ‘attachment to neighbourhood’ found that the sense of community can be affected by both physical (e.g. housing, traffic green spaces) and social (e.g. community size, type and density) aspects of the environment28,29,30.Most of the previous studies have used population-based surveys or questionnaires to explore prevalence of loneliness (e.g. BBC’s Loneliness Experiment) or how loneliness affects aspects of mental or physical health4. While these studies have traditionally focussed on loneliness as a stable emotional state, recent studies have begun utilising advancing technologies to explore dynamic changes in loneliness as people go about their daily lives31,32. Although one might have a general feeling of loneliness, as with all emotional states, this is unlikely to be a static condition; in particular, a feeling of loneliness at a given moment may be influenced by changes in the surrounding social and built environment. In addition, while previous studies have investigated the link between loneliness and certain features of the environment (e.g. overcrowding), few of them have explored how multiple aspects of the built and social environment may interact with each other to modify the feeling of loneliness. Lastly, many previous studies have relied on cross-sectional population-based surveys which do not collect real-time information as people go about their daily lives, thus limiting ecological validity and largely overlooking dynamic changes over time33.To assess the dynamic changes over time, the present study employs the Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) methodology to record individual experiences in ‘real-time’34,35. This makes EMA particularly well-suited to record the effects of the environment as it is experienced, reducing recall biases while increasing ecological validity. In particular we used the Urban Mind smartphone application (https://www.urbanmind.info;34) to investigate how social (i.e. perceived overcrowding and social inclusivity) and physical (i.e. contact with nature) aspects of the environment affect the feeling of loneliness in the moment. In addition, while most of the past studies focused on discrete populations, here we employed a large convenience sample of people in the general population (N = 2175) who have downloaded and used the Urban Mind app between April 2018 and March 2020.Our primary research aim was to shed light on the associations between social and built environment and loneliness. We hypothesised that (i) perceived overcrowding will be positively associated with momentary feelings of loneliness; (ii) perceived social inclusivity will be negatively associated with momentary feelings of loneliness; and (iii) contact with nature will be negatively associated with momentary feeling of loneliness. To provide an objective comparison to these findings, we also hypothesised that (iv) increased population density will be positively associated with momentary feeling of loneliness. Finally, we explored possible interactions of contact with nature on the associations between loneliness and perceived overcrowding, social inclusivity and objective population density.The current study received institutional review board (IRB) approval from the King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittees (LRS-17/18-6905). All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants confirmed they had read the study information and privacy policy and provided informed consent.Urban Mind appThe present study was conducted using data collected from an adapted version of the Urban Mind app. Detailed description an earlier version of the Urban Mind tool can be found elsewhere34, but a brief summary of the adapted version used in the current study is provided here. The Urban Mind app is a smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment tool available for both Apple iPhone and Android devices. Participants were recruited globally, over a period of 24 months (April 2018–March 2020) using various social media platforms, the project-related website, and by word of mouth. Participation in the study was self-selected and anonymous. Once an individual downloaded and installed the app, they were presented with information about the study and were asked to provide informed consent. After consent was provided, participants were requested to complete a baseline assessment. This baseline assessment collected information regarding demographics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity), socioeconomics (e.g. education, occupation), sleeping patterns (e.g. usual wake and sleep times) and self-reported mental health history (e.g. current and past mental health diagnoses).Following the baseline assessment, the app scheduled a total of 42 ecological momentary assessments during the following 14 days (3 assessments per day). These assessments were scheduled based on the participants’ baseline-reported sleep schedule. The timeframes when the participants were awake were divided into 3 equal intervals, and an assessment was randomly scheduled within each window. Once an assessment was available, the app would prompt a participant to respond within 1 hour before the assessment was marked as incomplete. This allowed users to complete the assessment while minimising interruptions to their everyday activities. These momentary assessments collected information about an individual’s perceived built and social environment, and their location via GPS-based geotagging. After each assessment, participants were prompted to capture and submit a photograph of the ground and an 8-s audio clip of their surrounding environment. These images and audio clips were not included in the statistical analysis but were used to promote participant engagement and disseminate the project on our social media and website (www.urbanmind.info).ParticipantsDuring the 24-month recruitment period, 2175 participants downloaded the Urban Mind app and completed the baseline assessment. Of this sample, 756 participants completed at least 25% of the assessments (a minimum of 11 out of 42 assessments), 397 participants completed at least 50% of the assessments (21 out of 42 assessments), and 113 participants completed at least 75% of the assessments (32 out of the 42 assessments).MeasuresOvercrowdingPerceived overcrowding derived based on a single item, ‘Does it feel overcrowded where you are right now?’, within each Urban Mind momentary assessment. Participants could respond with either ‘No’, ‘Not sure’ or ‘Yes’. Perceived overcrowding was utilised as a binary variable within analyses, with ‘No’ and ‘Not sure’ combined into a category (0) and ‘Yes’ as the other category (1).Perceived social inclusivityMomentary feelings of social inclusivity were derived from the sum of 3 questions during each Urban Mind momentary assessment. The items asked participants to think about the people in the neighbourhood at the time of the assessment: (1) ‘Do you feel welcome amongst them?’ (2) ‘Do you feel they would be willing to help you?’ and (3) ‘Do you feel they share the same values as you?’.Participants responded with either ‘No’ (1), ‘Not sure’ (2) or ‘Yes’ (3), and the scores were summed to create a ‘social inclusivity’ score ranging between 3, indicating low perceived social inclusivity, and 9, indicating high perceived social inclusivity.Contact with naturePerceived contact with nature was derived from 5 items in the Urban Mind assessments: (1) ‘Can you see plants right now?’ (2) ‘Can you see trees right now?’ (3) ‘Can you see the sky right now?’ (4) ‘Can you see or hear birds right now?’ and (5) ‘Can you see water right now?’. Participants could respond to each of the questions with either ‘No’, ‘Not sure’ or ‘Yes’. Contact with nature was included in our models as a binary variable, with ‘No contact’ (0) if a participant answered either ‘No’ or ‘Not sure’ to all 5 nature questions, or ‘Contact with nature’ (1) if a participant answered ‘Yes’ to at least one nature question.Population densityObjective measures of population density of each Lower-layer Super Output Area (LSOA) within England and Wales were obtained from the Office for National Statistics36. These measures, population per total square area of the LSOA ((frac{persons}{{km}^{2}})), were estimates of usual resident population from mid-2018 and ranged from the least densely populated LSOA of 2 persons/km2 to the most densely populated LSOA of 102,692 persons/km2. A subsample of Urban Mind assessments completed within England and Wales were spatially linked to the corresponding LSOA and population density value for that LSOA. The population density values of the 1307 LSOAs included in our sample were divided into deciles for the current analysis (see Fig. 1 for approximate locations of Urban Mind assessments completed within England and Wales and an LSOA resolution population density heatmap). Time-varying population density exposures over 14 days of the sub-sample of participants in England and Wales who completed more than 75% of assessments are reported in Supplementary Fig. 1.Momentary lonelinessFeelings of momentary loneliness were assessed using a single, 5-point Likert-scale item regarding an individual’s feelings during the momentary assessment: ‘Right now I am feeling lonely’. The participant would select a response ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘Strongly agree’ (5).CovariatesTo account for the effects of potential confounders, the statistical models were adjusted for covariates. This included participant demographic information collected during the initial baseline assessment, such as age, gender, ethnicity, education and occupation.Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed with STATA/SE 15. Longitudinal associations between momentary feelings of loneliness and self-reported perceive

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-03398-2

Lonely in a crowd: investigating the association between overcrowding and loneliness using smartphone technologies