Leisure-time physical activity and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in Chinese retired adults Xuanwen Mu1 na1, Kuai Yu1 na1, Pinpin Long1, Rundong Niu1, Wending Li1, Huiting Chen1, Hui Gao1, Xingxing Li1, Yu Yuan1, Handong Yang2, Xiaomin Zhang1, Mei-an He1, Gang Liu3, Huan Guo1 & Tangchun Wu1 Scientific Reports 11, Article number: 24202 (2021) Cite this article CardiologyDisease preventionEpidemiologyRisk factors The optimum amounts and types of leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) for cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention among Chinese retired adults are unclear. The prospective study enrolled 26,584 participants (mean age [SD]: 63.3 [8.4]) without baseline disease from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort in 2013. Cox-proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). During a mean 5.0 (1.5) years of follow-up, 5704 incident CVD cases were documented. Compared with less than 7.5 metabolic equivalent of task-hours per week (MET-hours/week) of LTPA, participating LTPA for 22.5–37.5 MET-hours/week, which was equivalent to 3 to 5 times the world health organization (WHO) recommended minimum, was associated with a 18% (95% CI 9 to 25%) lower CVD risk; however, no significant additional benefit was gained when exceeding 37.5 MET-hours/week. Each log10 increment of MET-hours/week in square dancing and cycling was associated with 11% (95% CI 2 to 20%) and 32% (95% CI 21 to 41%), respectively, lower risk of incident CVD. In Chinese retired adults, higher LTPA levels were associated with lower CVD risk, with a benefit threshold at 3 to 5 times the recommended physical activity minimum. Encouraging participation in square dancing and cycling might gain favourable cardiovascular benefits. Physical inactivity is one of the major modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD)1,2, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally3,4. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends every adult to maintain a minimum of 150 min of moderate-intensity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity activity per week, which is equivalent to 7.5 weekly metabolic equivalent of task-hours ([MET]-hours/week) of physical activity (PA), to experience health benefits5. However, almost one-fourth of the adults worldwide did not meet such recommendations6, and even more failed to achieve these levels in post-retirement population7,8. In addition to the declining physical function with advancing age9,10, pattern and amount of PA in retired adults differ greatly from that in their working counterparts, mainly characterized by a marked reduction in occupational and transportation domains of PA and higher participation in leisure-time physical activity (LTPA)7,11. Thus, identifying the optimal amount and type of LTPA for retired adults has become a key priority to guide future recommendation and optimize CVD prevention.Cumulative studies from western countries have suggested that recreational activities might be more effective to offset the risks of CVD in older adults12,13,14. However, the prospective evidence remained limited regarding the association between incident CVD and recreational activities with Chinese characteristics, such as square dancing, a popular activity enjoyed widespread popularity among middle-aged and older Chinese15,16. Furthermore, the prolonged sedentary time in retired adults during the past decades is increasingly striking, which also contributes to an elevated risk of CVD17,18,19. Recent prospective study reported that more activity might attenuate the detrimental association of prolonged sedentary time with CVD20. However, most of the previous studies assessed merely common sedentary behaviour such as watching TV21,22; it remains unclear about the relation between Mahjong and health status among Chinese23.In the present study of retired adults from the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort, we examined the association of LTPA with the risk of incident CVD and its major components. We also evaluated the dose–response associations of CVD with total and different types of LTPA separately. Additionally, we investigated the association of combined categories of sedentary behaviour and LTPA with the risk of CVD.Of the 26,584 participants (43% male and 57% female; mean [SD] age: 63.3 [8.4] years) included in the present study, the median LTPA was 21 MET-hours/week (interquartile range, 11.3–42 MET-hours/week), and 18.2% of the participants (n = 4832) did not meet the WHO recommended PA minimum (< 7.5 MET-hours/week) at baseline. In general, the most common type of leisure activity performed by retired adults was walking (77.7%), followed by square dancing (10.8%), jogging (5.0%) and cycling (4.7%). Table 1 showed the baseline characteristics of study participants according to LTPA categories. Comparing with inactive participants, those with higher levels of LTPA were tended to be educated more, smoke less, drink more, eat more fruit and vegetables, have lower BMI, and have less sedentary time (P 37.5 MET-hours/week; HR, 0.81 [95% CI 0.73 to 0.90]). The adjusted HRs (95% CIs) for CVD across categories of LTPA (7.5 to ≤ 22.5, 22.5 to ≤ 37.5, > 37.5 MET-hours/week) were 0.93 (0.86 to 1.01), 0.82 (0.75 to 0.91) and 0.81 (0.73 to 0.90), respectively (Ptrend 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S1 online).Table 2 The association of leisure-time physical activity with cardiovascular disease.Cubic spline analysis showed that any level of LTPA was associated with significantly lower risks of CVD and stroke (PCVD < 0.001, Fig. 1A; Pstroke < 0.001, Fig. 1C). Each one increment in log10 (MET-hours/week) was associated with 11%, 8%, and 20% lower risks of CVD (HR 0.89 [95% CI 0.84 to 0.95]), CHD (HR, 0.92 [95% CI 0.86 to 0.99]), and stroke (HR 0.80 [95% CI 0.69 to 0.92]), respectively (Fig. 1). Compared with no baseline LTPA, the most rapid decrease in CVD risk was seen before 3 times the WHO recommended minimum of PA. For total LTPA, the risks decreased by 8% for CVD (95% CI 2 to 14%) and 21% for stroke (95% CI 8 to 32%), respectively at 3 times the recommended minimum.Figure 1Adjusted hazard ratios for CVD, stroke and CHD according to levels of leisure-time physical activity. (A) Association between leisure-time physical activity and incident CVD. (B) Association between leisure-time physical activity and incident CHD. (C) Association between leisure-time physical activity and incident stroke. The multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking status, alcohol intake, consumption of food (meat, vegetables, and fruit), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, BMI, total sedentary time, and family history of CVD.Association between different types of LTPA and incident CVDWhen examining specific types of LTPA, a monotonic decrease in CVD risk was seen with increasing levels of square dancing (Each one increment in log10 [MET-hours/week]: HR, 0.89 [95% CI 0.80 to 0.98]; Fig. 2B), and such association was mainly restricted to female (P = 0.014; Supplementary Fig. S2 online). However, For cycling, we identified a U-shaped curve for the association, with the maximum observed cardiovascular benefit accrued with 37.5 MET-hours/week, equivalent to about 9 h cycling per week (HR, 0.46 [95% CI 0.33 to 0.63]); Fig. 2C). No significant association was seen for other types of LTPA (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S3 online).Figure 2Adjusted hazard ratios for CVD according to levels of different types of leisure-time physical activity. (A) Association between walking and incident CVD. (B) Association between square dancing and incident CVD. (C) Association between cycling and incident CVD. The multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking status, alcohol intake, consumption of food (meat, vegetables, and fruit), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, BMI, total sedentary time, other LTPA, and family history of CVD.Interaction between LTPA and sedentaryParticipants reported prolonged time spent playing Mahjong have a significantly higher risk of incident CVD in comparison with those not playing (HR comparing extreme categories, 1.09 [95% CI 1.00 to1.18]; Ptrend = 0.022), whereas no significant association was observed for screen activities (HR comparing extreme categories, 0.98 [95% CI 0.81 to1.20]; Supplementary Table S2 online). In addition, our findings showed significant additive interactions of LTPA and playing Mahjong for incident CVD (Padditive interaction = 0.037; Fig. 3A), no significance was found for screen activities (Padditive interaction = 0.411; Fig. 3B). Compared with the most active participants (i.e., those with more than 36 MET-hours/week), those in the bottom LTPA tertile had a significantly higher risk of CVD, regardless of time spent playing Mahjong. No such association was seen for screen activities.Figure 3The joint effect of LTPA and sedentary behavior on incident CVD. (A) The joint effect of LTPA and Mahjong playing on incident CVD. (B) The joint effect of LTPA and screen activities on incident CVD. The multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, education, smoking status, alcohol intake, consumption of food (meat, vegetables, and fruit), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, BMI, MET-hours/week, and family history of CVD. *P < 0.05. †The number was 26,354 for Mahjong and incident CVD analysis; the number was 26,558 for screen activities and incident CVD analysis. ‡The hazard ratios (95% CI) from the most active to the least active group were: 1 (reference), 1.06 (1.00 to 1.16), 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24), 1.05 (0.90 to 1.21), 1.12 (0.96 to 1.30), 1.24 (1.07 to 1.44), 1.05 (0.90 to 1.21), 1.13 (0.97 to 1.32), 1.26 (1.08 to 1.47), respectively, in (A). ¶The hazard ratios (95% CI) from the most active to the least active group were: 1 (reference), 0.78 (0.45 to 1.35), 0.80 (0.51 to 1.25), 0.81 (0.57 to 1.14), 0.84 (0.59 to 1.19), 0.91 (0.64 to 1.30), 0.75 (0.53 to 1.07), 0.85 (0.60 to 1.22), 0.88 (0.61 to 1.25), respectively, in (B).In this prospective study of Chinese retired adults, our results supported that meeting the WHO recommended minimum was associated with significantly lower CVD risk and further suggested the optimal benefit by reaching 3 to 5 times the recommended minimum. Encouraging retired adults to participate in square dancing and cycling might gain favourable cardiovascular benefits. Interestingly, we found that those with high LTPA level might mitigate the excess risk of CVD associated with sedentary behaviour, particularly playing Mahjong.Our finding of reduced CVD risk associated with higher LTPA level was consistent with previous studies24,25,26,27,28. A historically prospective cohort study of 416,175 healthy individuals from Taiwan found that, compared with inactive individuals, those who were meeting PA recommendations had a 32% lower risk of CVD mortality (HR, 0.68 [95% CI 0.61 to 0.76])29. A pooled analysis (661,137 participants, about 14.2 years follow-up) found the benefit threshold of a 42% lower risk of CVD mortality (HR, 0.58 [95% CI 0.56 to 0.61]) with LTPA of 3 to 5 times the recommended minimum (22.5–40.0 MET-hours/week) compared with no LTPA30. Furthermore, another study of 88,140 US adults indicated that no additional cardiovascular health benefit was found when doing more than 10 times the recommended LTPA31. Despite focusing on working adults, these studies investigated only fatal CVD, and the present study of retired adults further extended previous findings by showing appreciable benefits related to incident CVD when exceeding the WHO recommendations. The beneficial effect in male might because that the LTPA level was higher than that in female (mean [SD]: 35 [36] in male and 31 [32] in female; P < 0.001). The relatively lower risk of stroke associated with LTPA observed in our study was in line with the effect of walking in the cohort study with 73,265 participants32 and another Japanese study with 74,913 participants25, which might be due to the better improvement of cerebral blood flow and perfusion through LTPA33.The interesting finding was that square dancing was associated with a lower CVD risk. A cross-sectional study of 1944 adults in China found a 30% lower prevalence of CHD among adults with moderate or high frequency in walking or square dancing34. To date, only one prospective cohort study of 48,390 British adults, reported that dancing was associated with a 46% lower risk of cardiovascular mortality during a mean of 9.7 years of follow-up35. The present study found that a monotonic decrease in CVD risk with increasing levels of square dancing. Despite the different outcomes (CVD mortality versus incidence) investigated, the lacked consistency in the magnitude of CVD benefits could be interpreted by the between-racial differences in intensity of dance performed in China and western countries. Square dancing, a popular LTPA type in China, can be easily accepted by low-income people36. The superior benefits of square dancing over other types of leisure activity may be due to the lessened daily mental stress through its direct social and entertaining components37. To our knowledge, the present study was the fir

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-03475-6

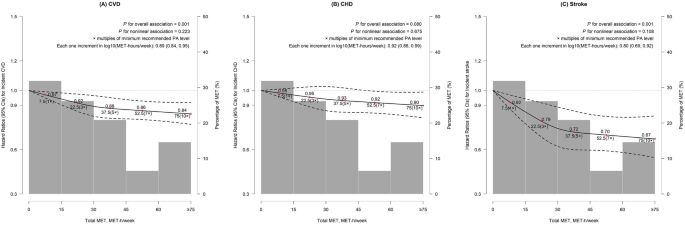

Leisure-time physical activity and risk of incident cardiovascular disease in Chinese retired adults