The SPI shares its science, technology and stewardship principles with the SHI, a headline indicator in the draft GBF that addresses Goal A milestones on the integrity of ecosystems and the health and genetic diversity of species population11,23,24 (https://www.post-2020indicators.org). The SHI’s measurement of change in area and connectivity of suitable habitats relative to a baseline builds on extensively used related approaches assessing conservation policies11,25. Both metrics connect local data — as published from national monitoring or citizen science (for example through GBIF, https://www.gbif.org) — to globally comparable indicator metrics via EBVs, and both support disaggregation to single species and kilometre-pixel planning units. Availability of suitable habitats is the key and broadly quantifiable determinant of population size, but other factors can affect local abundance and, where available, surveys can be used to refine this link. Detailed maps, links to underpinning data and transboundary context are provided through Map of Life (https://mol.org/indicators), and globally standardized national indicator values and metadata are available there or through GBF-associated dashboards. The EBV-based nature of the SPI and SHI and their empirical design following FAIR principles (findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable) enable transparency and substitution at any level from data to indicator and supports the independent use of national monitoring data and workflows. Countries can also leverage national information on species representation or habitat quality and use the same indicator methodology to independently generate SPI and SHI values using their own data or to address species of particular national interest (for example, as underway in Colombia, http://biomodelos.humboldt.org.co). Additional capacity support and training has the potential to strongly increase such bottom-up development and local co-ownership. These indicators are among a growing set, many of them developed in association with GEO BON (https://geobon.org/ebvs/indicators), that use new scientific data integration approaches to leverage novel data flows, such as from remote sensing and global data networks. Other examples include the Rate of Invasive Alien Species Spread Indicator26 and the Biodiversity Habitat Index27. These types of products complement a previous generation of legacy indicators that are more qualitative (such as categorical species threat status or stand-alone high-value biodiversity areas) and by design less geographically representative, scalable and/or responsive to short-term change. By leveraging ongoing data flows, the new indicators can account for and provide planning support in concert with dynamic processes such as species range shifts from climate and land-use change. The necessarily quantitative and global nature of these indicators can represent impediments for bottom-up development and local co-ownership without capacity support. In our view, these challenges are not insurmountable given the value these indicators bring to better understanding how our conservation actions and interventions impact biodiversity. For the SPI and SHI, some challenges are helpfully addressed through the transparent use of species as base units, the potential for fully independent national calculation (for example, using national species information and/or land cover products), and the long-term data, measurement and usage support provided through GBIF, Map of Life and GEO BON.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01620-y

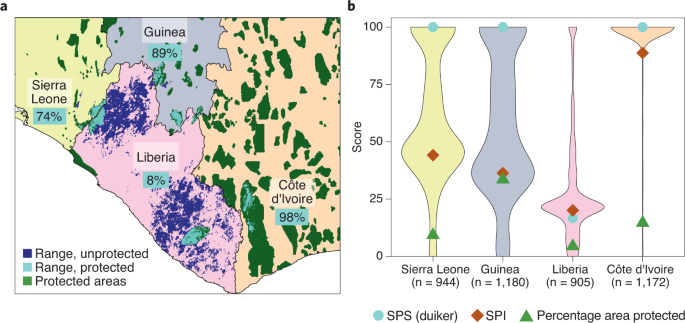

Include biodiversity representation indicators in area-based conservation targets