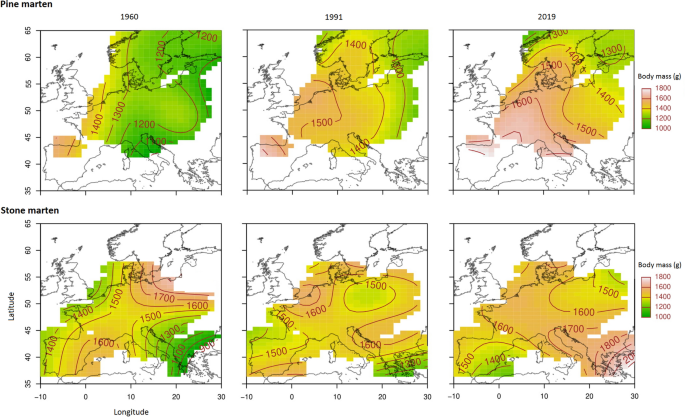

Using data from a large database of body mass measurements distributed over a vast geographical area and a period of almost 60 years, we found that pine marten body mass decreased with increasing latitude and increased with time. A similar trend for both spatial and temporal variation in pine marten body size suggests that the same factor or combination of factors drive these changes. In contrast, geographic variation of stone marten body mass showed a more complex spatio-temporal pattern that varied across regions. These different rates of body mass changes occurring over time and space in both marten species affected the body mass ratio between the species and may have increased interspecific competition in local populations. A higher body mass increase in sympatric areas compared to allopatric areas contradicted our prediction that body mass increase was limited by interspecific competition. This might have been caused by confounding patterns in climate change intensity and productivity increase, with continued limited productivity in the allopatric part of the stone marten range. In addition, pine marten body mass increase was lower in the allopatric area, despite a greater productivity increase and temperature warming than in the sympatric area, which is also contrary to our predictions. Therefore, our results suggest the importance of interspecific competition in body mass changes in response to climate change.

Body mass is commonly used as an index of animal body size41, but this metric also includes body condition, which varies within an individual’s lifetime and may give different results than a structural size metric only42. However, martens have limited possibility to accumulate fat reserves and they rely little on body energy reserves43. Thus, we expect that a significant portion of body mass increase will be due to an increase in structural body size. This prediction was confirmed by a recent study suggesting increase in a skull morphometry, as a proxy of body size, in pine marten44. The study spanned the last 117 years, but an increase in body size had occurred from around 1960, exactly in line with the results of this study. Therefore, we assume that the body mass increase at a large geographical scale obtained in this analysis resulted largely from a structural size increase and only in minor part from an increase in body condition.

The increase in body size over time may result from two mechanisms: (1) an increase in productivity can provide an increase and more stable food base that causes an increased growth rate in juvenile animals and the increased survival of larger individuals and/or (2) a release from the constraint of extreme winter temperature increases the survival of larger individuals. In several species, the adult body size is a result of the length of the period when high-quality food is taken during growth45,46. Thus the mean increase in body mass of both pine and stone marten over time might have been caused by the observed increase of primary production and food abundance appearing with climate warming at mid- and high-latitudes47. The increasing abundance of berry shrubs in forests as a result of climate change48 may enhance the availability of main pine marten prey49 due to the positive correlation between berry and rodent densities50,51. Higher rodent density may positively affect pine and stone marten body mass. This suggestion was confirmed for the American marten (Martes americana), which increased in size between 1949 and 1998 in Alaska. The increase was explained by lower energy expenditure and improved food availability, considered as the increase in annual net primary production, which led to larger rodent populations52. Besides climate change, food availability can be affected by land use changes over time, such as deforestation and habitat fragmentation53.

Secondly, larger individuals may be released from low temperature constrains due to climate change. Winter thermal stress is the most important factor affecting the duration of pine marten daily activity54. To optimize their energy budget and reduce heat loss at low temperatures, pine martens reduce activity and select well-insulated resting sites during the day, while satisfying their food requirements by shifting to feed on ungulate carrion and/or hunting larger prey species and storing the food54,55. Then, a smaller body probably results in higher survival due to lower energy needs56,57. Increasing winter temperatures may release pine martens from this restriction, and larger individuals may potentially survive winters more often, which could have caused the increase in body size over time. Built-up areas utilised by stone marten provide well-insulated resting sites and additional food sources (e.g. rodents, food waste, fruits) within buildings, which allow stone martens to avoid the pressure of severe weather conditions. A recent study found that body mass of mammals was greater in areas with higher index of urbanization58. Stone marten body size could have already been higher during past periods of colder climate and increase only slightly with climate warming.

Summarizing, both potential reasons for the increase in martens body mass over time, an increasing productivity and a release from winter temperature constraints, are not mutually exclusive. Higher food abundance allows an increased rate of growth in juvenile individuals which can then achieve a larger body size. At the same time, warming temperatures allow martens with larger body sizes to survive the winter more easily, when larger individuals would otherwise need to maintain a greater body size while also reducing activity to avoid exposure to the lowest temperatures.

The increase in body size across the geographical scale (over space) seems to be determined by the same force affecting temporal variation in body size of the studied species. In our dataset, the body mass of pine martens increased towards the south, consistent with previous analyses of geographical variability of this species showing that pine martens are larger in warmer geographical regions13,39. We found a less clear spatio-temporal pattern of body mass variability for stone marten, which was more ambiguous and the increase of body mass over time varied between locations. These spatial variations might be due to (1) the stone marten inhabiting various habitats in different locations, (2) the ongoing range and demographic expansions of stone martens in some locations in Europe, and (3) the varying competitor community structure across the stone marten range. In western Europe, stone martens inhabit natural habitats36, and their body mass highly increased over time in this region. In central Europe, stone martens inhabit cities, villages, and fragmented forest-field landscapes36. In these habitats, stone marten body size could vary due to, e.g., differences in food availability as well as in predation and competition pressure. Built-up areas provide well-insulated resting sites and additional food sources (e.g. rodents) within buildings, which allow stone martens to reduce their activity outside of buildings, and thus, avoid the pressure of severe weather conditions. It is possible that a body size threshold exists and it could have already been higher during past periods of colder climate and increased only slightly with climate warming. Furthermore, changes in agricultural production and management of the landscape over time might have improved the diet of carnivores commensal with humans and caused the increase in their body size59.

The body mass of stone martens decreased in two regions of its range. In north-eastern Europe, stone martens recently expanded their range60. At the beginning of a range expansion, larger animals can disperse, further colonizing new areas where, due to low density, intraspecific competition is low and body mass is larger61,62. The increase in stone marten density in this region might have increased intraspecific competition that could have caused a body mass decrease over time. Such a decrease of body mass, during a period of population establishment and demographic expansion, was observed in American mink (Neovison vison) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in Europe63,64. Stone marten body size also decreased on the southern Iberian Peninsula, but the mechanism driving this change is unclear. All these factors confounded our results to a varying extent, causing a weaker response of stone marten body size to latitudinal climate variation and temporal climate warming.

Our results show that the stone marten was heavier than the pine marten, except on the northern Iberian Peninsula, where the stone marten is lighter than the pine marten (see Fig. 4a, site S2). The co-occurrence of mesocarnivores is driven largely by the relative body size of the species, while trophic relationships or food availability seem to be less important31. Previous studies suggested that the stone marten can be outcompeted by the pine marten, especially in forested habitats and in Mediterranean climate65,65,67. The competitive advantage of the pine marten on the Iberian Peninsula is likely driven by a combination of bigger size and the occurrence of the common genet, which competitively displaced the stone marten from areas with dense vegetation68. However, in other parts of Europe, the stone marten generally had a competitive advantage in body mass over the pine marten. We found that the body mass of pine martens increased faster than that of stone martens over the last 59 years, and for pine marten this increase is greater in sympatric than allopatric areas despite the fact that climate is warming faster in allopatric areas (north Europe) than sympatric areas (central Europe)69. However, due to the limited allopatric range of both species, these results should be treated with caution. As a consequence of faster body size increase in sympatric areas, the body mass difference between both marten species has narrowed over time and even turned in favour of the pine marten in five sites. The release from a temperature constraint could probably promote the competitive advantage of larger pine martens, causing a further increase in pine marten size in areas where they occur alongside larger competitors. Such competitive advantage has previously been suggested, as polecat body size increased after the introduction of a larger competitor, the American mink62. The apparent similarity in stone and pine marten body mass may strengthen competitive interactions between both species.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-03531-1