Data

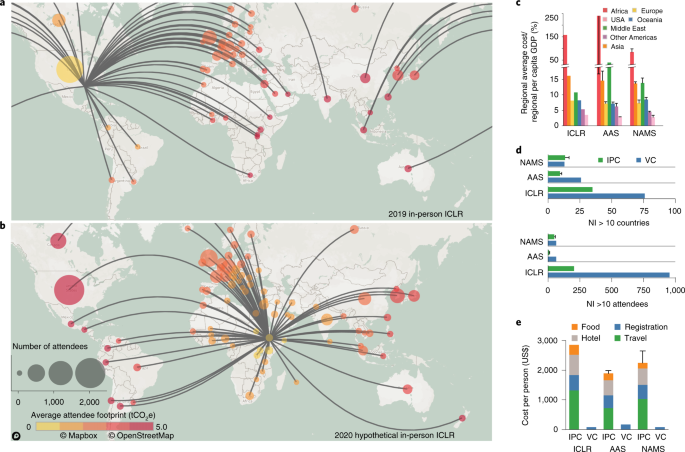

Registration, digital platform and survey data were collected from three IPCs-turned-VCs and are presented in Supplementary Table 21. The three analysed IPCs-turned-VCs include the annual ICLR (~2,300 historical average attendees), the AAS summer meeting (~700 historical average attendees) and the NAMS annual conference (~450 historical average attendees). Complementing this are data from the POMs (~1,000 attendees) and the IWA (~350 attendees), conference series that were specifically designed for the virtual ecosystem. These conferences represent varying fields and community sizes and allow for comparisons across a range of STEM backgrounds. Data for IPCs-turned-VCs were collected for 2020 VCs and for historical IPCs. POM and IWA data provided a control for an always VC, while the baseline data for historically IPCs allowed for the elimination of effects from other variables, facilitating direct analysis of the impact that virtual components had on conference performance.

Specific data collected include registration and abstract information, spanning information such as the number and type of participants (for example, students and industry personnel), geographic participation, institution and gender. For IPCs-turned-VCs, these data were collected for registrations accrued before and after moving online. Carbon footprint and cost of attendance were estimated on the basis of attendee work locations and conference destinations. Descriptive statistics11 and thematic mapping12 were applied to understand changing sociodemographics realized in the shift to a virtual format. Additional data collected on webinar attendance and virtual platform activity were used to assess the efficacy with which the VCs distributed content to attendees. Qualitative data were collected by asking participants to fill out polls as well as pre- and postconference surveys designed to interrogate the participant experience and field suggestions for improvement. Surveys were also used to investigate the impact of travel burden and cost barriers for female versus male NAMS attendees. Survey questions included multiple-choice and open-ended questions about specific conference components and the participant experience. The surveys were produced by the authors for the conferences that they organized. Survey and polling questions underwent IRB review receiving and exempt status (protocol 2020-05-0026) at The University of Texas at Austin.

Sociodemographic data were provided by conference organizers and filled in as necessary. Attendee countries were manually categorized by region for analysis. Job-type data (that is, graduate student, industry personnel) were provided by conference organizers via registration or survey data. Data that included specific job titles (that is, operations director, research scientist) for attendees were categorized manually by job type. Gender data were provided by organizers for some conferences via voluntary surveys. Gender data for the NAMS conference were manually assigned on the basis of author familiarity with the participants and through internet search of attendee names. The Gender API13 was also used to assign gender to attendee names for NAMS and AAS conference attendees. Due to confidence in the accuracy of manually assigned names for NAMS attendees, discrepancies in the genders assigned to NAMS attendees by the manual process and the Gender API indicated that the Gender API was less accurate than the manual process (Supplementary Table 8). Consequently, the Gender API was only applied to assign gender to AAS participants. Attendee academic institutions were manually categorized according to databases of institution types. Minority serving institutions were defined according to the 2007 US Department of Education database14. High research institutions (R2) were defined as any institution that was included in the 2018 Carnegie classification of R2 universities15. PUI were defined as any university that awarded 20 or fewer PhD degrees in NSF-supported fields during the combined previous two academic years16 as reported by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) records on PhD degrees for major science and engineering fields awarded by universities during 2017 and 201817,18. Non-research-intensive countries were defined as countries that were not in the top ten countries for scientific research as defined by the NI that measured top countries in terms of contributions to papers published in 82 leading journals during 2019 (NI > 10) (ref. 8).

Travel distance

Attendee travel distance, carbon footprint and cost were calculated via python scripts using attendee origin location data provided by conference organizers. NAMS and AAS registrant origin locations were provided by organizers via registration data as a list of attendees with attendee-specific locations. If location for an attendee was not included, origin location was determined via internet search of the attendee name. ICLR and POM registrant origin location data was provided by conference organizers and comprised a list of countries in attendance and the number of attendees from each country. While the sample size of data for single ICLR conferences varied by data type (origin country, gender and job title), origin country was the largest dataset for all ICLR conferences and was thus assumed to be the true size of the conference delegations.

Conference city and attendee origin coordinates were determined by querying the Google Maps API19 with the location names. If a city-specific attendee origin was not recognized by the API, the attendee origin was set to the attendee’s origin country name. Google Maps API queries of only country name return coordinates for the geographical centre of the country. Travel distance between attendee origin and conference location were calculated as the great circle distance (great_circle python package).

Carbon footprint of attendance

The carbon footprint of conference attendees was calculated for all IPCs-turned-VCs as the cumulative emissions associated with the flight and hotel stay. The air travel carbon footprint was calculated according to the methodology for the myclimate air travel emissions calculator20. The myclimate calculator computes air travel footprint by adding 95 km to the great circle distance to account for flightpath inefficiencies and calculating GHG emissions associated with the fuel burn and life-cycle footprint of the airplane and associated aviation infrastructure. The GHG emissions are then converted to CO 2 e. It was assumed that all conference attendees flew economy class. If city-specific attendee origin data were available and the attendee was local (≤100 km from the conference city) it was assumed that the attendee did not fly to the conference city and their travel CO 2 e was set to 0. If registrant origin coordinates were not found, the attendee travel distance and travel footprint were set to the average for that conference.

The carbon footprint per night for the attendee hotel stay was determined using the Hotel Carbon Measurement Initiative (HCMI) rooms footprint per occupied room from the Hotel Sustainability Benchmarking Tool published by the Cornell Center of Hospitality Research21. The tool provides city-specific and country-specific footprint data. If data were not available in the Hotel Sustainability Benchmarking Tool for the conference city, then the footprint per night was set to the country average in the tool. If no data were available for the country in which the conference was held, the footprint was set to the value that was closest to the conference location geographically. Student hotel footprint calculations were adjusted to assume shared hotel rooms, that is footprint per night was divided by two. If attendee-specific job title (student versus non-student) information was not available, percentage of students as defined by the voluntary survey data was multiplied by the number of attendees from each country to estimate the number of students from each country. When computing total hotel footprint, it was assumed that attendees stayed for all but one night of the conference (so, for a four-day conference, nightly hotel footprint was multiplied by three). If the attendee was local, the hotel footprint was set to 0. If the attendee origin was not near the conference city and their job title (student versus non-student) was not known, the attendee hotel footprint was set to the conference average.

Cost of attendance

Cost of attendance for individual attendees was computed for historically IPCs-turned-VCs by calculating their cost of travel based on air travel distance and summing with the estimated cost of the hotel, food and conference registration fees. Travel cost was calculated as the one-way air travel distance multiplied by the cost distance for air travel defined in ref. 22 and doubled to represent the cost of a round-trip flight. If the registrant was local, their travel cost was set to 0. If the registrant origin was not known, the travel cost was set to the average conference travel distance and converted to cost using ref. 22. To account for a potential overestimate of travel cost, a sensitivity analysis where the one-way flight cost is multiplied by 1.5 instead of 2 was conducted and is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

NAMS hotel cost was taken from NAMS records. 2020 ICLR hotel cost was set to the average of hotel options provided by the ICLR website. For 2018–2019 ICLR and all AAS conferences, the cost of US hotels was set to the US General Services Administration lodging maximum per diem for the conference city. For 2018–2019 ICLR the cost of all hotels outside of the United States was set to the US State Department lodging maximum per diem for the conference city. Nightly hotel costs were divided by two for students to assume shared rooms. If attendee-specific job title (student versus non-student) information was not available, percentage of students as defined by the voluntary survey data was multiplied by the number of attendees from each country to estimate the number of students from each country. ICLR 2020 student hotel cost data were taken from ‘double room rate’ and ICLR 2020 non-student hotel cost data were taken from the ‘single room rate’ cost on the ICLR website. When computing total hotel cost, it was assumed that attendees stayed for all but one night of the conference (so, for a four-day conference, nightly hotel cost was multiplied by three). If the attendee was local, the hotel cost was set to 0. If the attendee was not local but their job title (student versus non-student) was not known, the hotel cost was set to the conference average.

Food cost for conferences held in US cities was taken from US General Services Administration city-specific per diem rates for breakfast, lunch and dinner. For NAMS, one dinner is subtracted from the total cost to account for the banquet dinner provided by NAMS. Food cost for conference cities outside of the United States was taken from US State Department city-specific meals and incidental expenses per diem. Attendees were assumed to stay for all but one night of the conference. If the attendee was local, food cost was set to 0. If the attendee origin was not known, the food cost was set to the conference average.

Registration costs for historical NAMS IPCs was set to the recorded registration fee per registrant. Fees for the sponsor and exhibitor registration types, where sponsors made their contributions via the registration fee, at historical NAMS conferences were set to conference average of that year (these registration types are excluded from the average).

Hypothetical registration fees for a 2020 NAMS IPC were assigned to attendees to the 2020 NAMS VC. The 2020 NAMS attendees with registrant type ‘student’ were assigned a hypothetical 2020 NAMS IPC registration fee equal to the average fee for students at the 2015–2019 NAMS IPCs (average based on title category, with ‘unknown/other’ title category excluded from the average). The 2020 NAMS VC attendees with registrant type ‘professional/academic’ were assigned a registration fee equal to the average fee for non-students at the 2015–2019 NAMS IPCs (average based on title category, ‘unknown/other’ excluded).

Student and non-student registration fees for 2018–2019 ICLR IPCs were set to early registration fees from the conference website. The registration fees for the 2020 ICLR VC were set to the 2018–2019 ICLR IPC average fees. As attendee-specific job title (student versus non-student) information was not available, percentage of students as defined by the voluntary survey data was multiplied by the number of attendees from each country to estimate the number of students from each country (total student registration fees by country = percentage of students from job title data × total attendees from country × student registration fee).

Registration fees for 2016–2019 AAS IPCs were set to the early registration fees for ‘full member/educator/international affiliate’, ‘graduate student member’, ‘undergraduate student member’, ‘emeritus member’ and ‘amateur affiliate’ from the 2020 winter meeting website. As attendee-specific job title information was not available, percentage for attendee job title as defined by the voluntary survey data was multiplied by the number of attendees to estimate the number of each job type in attendance. The total registration fee for each conference

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-021-00823-2