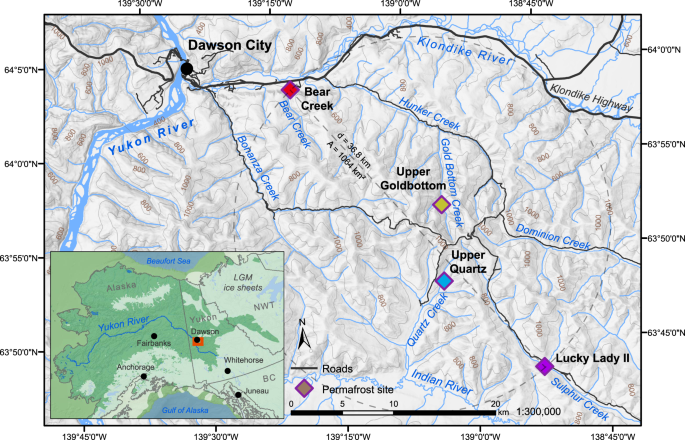

We observe four main trends within this dataset. (1) There is a surprising taxonomic richness and spatio-temporal consistency in the metagenomic signal across all sampling locations, suggesting that these reconstructions are representative of palaeoecological trends in the Klondike region. (2) Megafaunal sedaDNA declines gradually after the LGM with the Mammuthus primigenius signal being the first to drop out, followed by Bison priscus and Equus. (3) Signal dominance for forbs and graminoids is coeval with grazing megafauna, whereas the local transition towards woody shrubs is associated with a diminished faunal signal. Megafaunal sedaDNA reduces substantially after the Younger Dryas, by which time grazing megafauna had become functionally extirpated in the Klondike. (4) Despite this turnover, a low megafaunal sedaDNA signal persists into the Holocene. This signal—identified as a ghost range here—is suggestive of a late persistence of megafauna in a high latitude refugium, apparently outliving the functional extinction and complete loss of other continental populations.

Ecological turnover and collapse of the mammoth-steppe

Mammuthus, Equus, and Bison presence are closely associated in our dataset with forbs and graminoids characteristic of the mammoth-steppe biome. During the relative sedaDNA rise in Salicaceae (likely willow shrubs) ca. 13,500 and 10,000 cal BP, Asteraceae and Poaceae correspondingly decline in relative sedaDNA abundance while grazing megafaunal DNA largely disappears from our dataset. This suggests that, at least in the Klondike, Mammuthus primigenius may have been the first megafaunal species to undergo a local population reduction after ~20,000 cal BP.

It is difficult to say whether sedaDNA signal decay reflects an actual reduction in the regional abundance of animals or is reflective of other stochastic and unknown34 factors unique to this proxy such as variable eDNA release and turnover95, biochemical changes to eDNA stabilization processes such as organo-mineral binding90, or shifting microbial and other taphonomic pressures. As Equus sedaDNA remains relatively consistent until the rise of mesic-hydric woody shrubs during the Allerød warming (~13,500 cal BP) (Fig. 3B), this is suggestive of longer-term local declines of Mammuthus (and perhaps Bison) eDNA input rather than a shifting of biomolecular taphonomy because we would generally expect animal eDNA to breakdown or become mineral-bound88 at similar local rates. Further, Lagopus DNA spikes during major declines in megafaunal DNA. Again, implying local ecological rather than just taphonomic or methodological factors driving shifts in relative animal sedaDNA recovery. As this study used a capture enrichment approach targeting organelle genomes36 (with replicates [Supplementary Table 14]) rather than PCR metabarcoding amplicons76,112, relative changes in metagenomic signal abundance are arguably somewhat correlated with shifting eDNA inputs95,96,113,114,115,116 during periods of otherwise stable climate. As such, we suggest that major shifts in relative DNA abundance, such as Mammuthus sedaDNA nearly dropping out of the dataset after 20,000 cal BP, are ecologically informative.

The decline in local mammoth abundance that we infer from this sedaDNA record is consistent with a low frequency of 14C-dated mammoth macrofossils from the Klondike. M. primigenius macrofossils are comparatively rare in central Yukon relative to more northerly sites around Old Crow (Supplementary Fig. 1), but still relatively few of those northern macrofossils have been successfully radiocarbon dated because most are beyond radiocarbon range117,118. Much of the <30,000-year fossil record in Beringia is represented by a small number of well-preserved, and logistically accessible sites (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our faunal sedaDNA dataset somewhat conflicts with these macrofossil abundances in that the highest frequencies of DNA reads identified as Mammuthus, Equus, or Bison are distributed between 30,000–15,000 cal BP. Conversely, dated faunal remains of Mammuthus and Bison in eastern Beringia have a median concentration around 15,000 cal BP, with only Equus bones being predominant nearer to 25,000 cal BP (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Relative Bison and Equus sedaDNA signals decrease in read counts after ~15,000 cal BP. However, there is a subsequent increase around the onset of the Younger Dryas (ca. 12,900 cal BP) that may be associated with previously described Bison dispersals40,119 or other local factors (e.g. shifting mosaic vegetation patches25, herbivore land use, or taphonomy). It is worth noting that this inference is limited by there only being a single Younger Dryas core sample in this dataset. After the Younger Dryas (during the early Holocene) grazer sedaDNA nearly disappears (Fig. 3), which is correlated with the ecological turnover from forbs and graminoids to woody shrubs—predominantly Salix sp.—and a rise in avian fauna, rodents, and cervid browsers. There is a pronounced transition in the ecological signal after ~13,500 cal BP from forbs and graminoids to woody shrubs in the Lucky Lady II cores, with rises in Salix reads tightly associated with a sharp increase of Lagopus lagopus (willow ptarmigan) sedaDNA—a grouse whose habitat and subsistence patterns are based on woody shrubs120 (Fig. 3). Keesing and Young121 observed on the African savanna that when large grazing mammals were removed from an area, the rodent populations doubled, which increased the populations of predators that target small-bodied animals. Our data mirrors this observation with an increase in rodent sedaDNA after ~10,000 cal BP (Fig. 2), along with the appearance of the small forest dwelling carnivore Martes sp. (martens) who may also now be present because of trees on the landscape.

After Mammuthus primigenius and Equus sp. were functionally extirpated from the Klondike, the local ecosystem began transitioning towards boreal taxa with an associated rise in Picea (spruce) and mosses (Fig. 4). Despite significant declines in grazing megafaunal DNA, reads extend beyond their last dated macro-remains—perhaps even as late as the mid-Holocene—which has already been observed for Bison priscus39,40.

Our plant dataset is consistent with Willerslev et al.33 in which forbs were found to proportionally dominate their metabarcoded sedaDNA signal during and after the LGM. Nichols et al.112 argue that the forb dominance observed in Willerslev et al.33 was partly caused by polymerase and GC biases of their PCR metabarcoding approach favoring forbs over graminoids with the Platinum HiFi Taq polymerase targeting the short trnL (P6 loop) locus122. We have used a capture enrichment approach (indexed and reamplified with the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix) targeting much larger regions of the chloroplast genome (trnL [~500 bp], rbcL [~600 bp], and matK [~800 bp])36 where overall GC content is generally equivalent between the three major target families identified in Fig. 3 (see Supplementary Fig. 56). We suspect that beyond the PCR biases argued to have influenced Willerslev et al.33 (i.e. the greater relative abundance of forb sedaDNA compared to graminoids and woody plants) that this is likely the result of eDNA release and preservation characteristics of forbs with higher rates of biomass turnover. This more rapid turnover thus potentially leads to an eDNA over-representation of forbs compared with typical palynological findings. It has been argued that interpreting relative floral abundances with eDNA requires calibration. Yoccoz et al.95, for example, observed that their above-ground vegetation surveys were accurately mirrored in modern environmental soil DNA, but that functional groups (woody plants, graminoids, and forbs) varied in their proportional eDNA representation. Woody plants were most affected by this trend, being proportionally under-represented in eDNA compared to above ground biomass by 1:595, while graminoids were under-represented by 1:1.5. Conversely, forbs were over-represented by 2.5:1. GC and polymerase bias coupled with eDNA release variation, beyond simple growth form categories, complicates this further112. Nevertheless, the substantial abundance of forb DNA, even if cut by half, likely reflects an abundance of flowering herbs on the Pleistocene mammoth-steppe. This may also be under-represented palynologically due to varied pollen production between entomophilous (insect-pollinated) forbs and anemophilous (wind-pollinated) gramminoids123.

The rise in Pinaceae (notably spruce, see Fig. 4) around ~10,000 cal BP, and its growing dominance through our mid-Holocene samples, is consistent with other records from Yukon in regard to the initial development of the taiga/boreal forest124,125,126,127,128,129, and is consistent with pollen grains identified in samples younger than ca. 9200 cal BP (Supplementary Table 4). We observe similar relative sedaDNA increases in boreal flora (Fig. 4), albeit with a comparatively less abundant signal for Betula. Palynological studies frequently report an abundance of Betula with a comparatively small initial influx of Salix in the Alaskan-Yukon interior during the terminal Pleistocene shrub expansion125. While we observe a distinct rise in relative Betula sedaDNA during the Bølling–Allerød and post-Younger Dryas chronozones that persists into the Holocene, the number of Betula sedaDNA molecules are comparatively dwarfed by the immense abundances of Salicaceae (Salix [willow]) (Figs. 3–4) DNA. Betula is known to be over-represented by pollen, whereas Salix is often under-represented130,131,132,133. Our sedaDNA data suggests that Salix was more important in Beringian shrub expansion than palynological records have yet indicated.

The relative over-abundance of Salix sedaDNA compared to Betula is relevant to testing the shrub-expansion extinction model of Guthrie16, who contended that an increasing moisture regime and rise of mesic-hydric vegetation, with chemical defenses against herbivory (notably Betula nana exilis [resinous dwarf birch], but also including Salix)134,135,136, drove regional extirpations of grazing megafauna in eastern Beringia. If Salix was substantially more abundant in the Beringian shrub expansion than Betula as our sedaDNA dataset suggests, this questions whether the rise of defensive vegetation was a major driver in the extirpations as Salix is the most preferred and palatable shrub among extant subarctic browsers135,137. While Bison and Equus are considered closer towards the obligate grazer end of dietary guilds50,138, both have been observed to exhibit variable grazing and even mixed feeding139,140. Mammuthus, Equus, and Bison coprolites suggest that these taxa had a diet variably rich in forbs and graminoids, with a smaller but notable proportion of woody shrubs/trees (including alder [Alnus], birch [Betula], larch [Larix], spruce [Picea], and willow [Salix])33,141,142.

If mammalian sedaDNA abundances are rough indicators of palaeo-biomass (a correlation in need of further research), it is unclear why Mammuthus primigenius and Bison priscus (Fig. 2) relative sedaDNA signals decline prior to an expansion of woody shrubs during the Bølling-Allerød warming (Fig. 3). The abrupt increases in Cyperaceae (Carex [sedges]), Ericaceae (Arctous [bearberry], Rhododendron), Betulaceae, and Salicaceae during the Allerød are suggestive of a transition toward a moist dwarf-shrub ecosystem by ca. 13,500 cal BP. The presence of these plants suggests more continuous ground cover, better insulation, shallower permafrost, and likely boggy, wet conditions. The early Allerød rise of Fabaceae sedaDNA (particularly Astragalus and Oxytropis, Fig. 4) may also be indicative of a rise in flora with anti-herbivory defenses as these locoweeds are toxic to grazing fauna. Notably, despite otherwise rapid faunal and floral turnover, our single Younger Dryas core sample may suggest that the mammoth-steppe locally persisted through the Bølling-Allerød chronozone in the Klondike.

Mann et al.28,29 and Rabanus-Wallace et al.30 contend that a shifting moisture gradient from xeric to mesic-hydric, with the paludification of eastern Beringia, best accounts for the loss of dryland-specialists (Equus, Mammuthus), whereas mesic and mixed feeding seasonal fauna (Rangifer, Cervus, Ovibos) retained suitable habitats and hydric specialists (Alces, Homo sapiens) were able to invade new Beringian niches. While warming, an increasing moisture regime, the arrival of cervid browsers, and the rise of woody shrubs may explain much of the terminal signal decay observed for grazing specialists, this does not explain the relative declines of Mammuthus and Bison sedaDNA prior to the Bølling–Allerød chronozone (assuming that sedaDNA abundance retains a correlation with palaeo-biomass). Guthrie143 found that horses had undergone body-size declines after the LGM until their extirpation in Beringia, which likewise suggests longer-term pressures predating shrub expansion. The rise of woody plants in this dataset thus may be partially explained by both the gradual reduction in local megaherbivore ecosystem engineering over millennia and by a warming climate and shifting moisture regimes.

Unknowns in sedaDNA release, preservation, and recovery restrict what we can confidently infer from differences in relative signal abundance, but there are indications of both top-down and bottom-up contributions to the collapse of the mammoth-steppe in central Yukon. While the decline of faunal sedaDNA is likely influenced to some degree by shifting taphonomic processes (such as warming an

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-27439-6