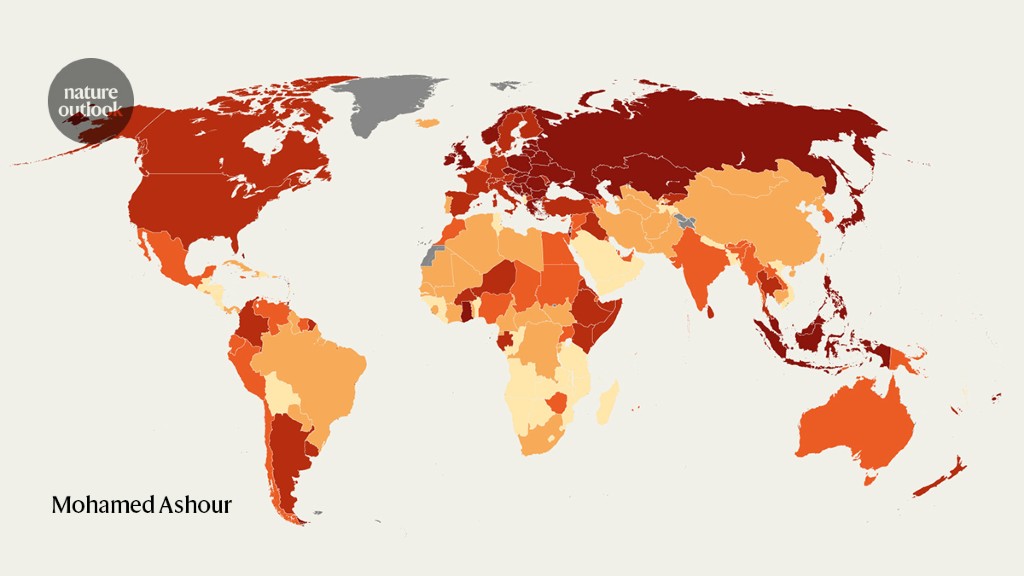

In one of the largest oncology clinics in northern Nigeria, a ragged notebook with torn, tattered pages serves as a patient-admission registry. ‘It is sad to see how data is currently being collected,’ says Aisha Mustapha, a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist at the Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital in Zaria. ‘It’s still manual data collection, which I know is unacceptable and will not give us adequate information.’Cancer registries are useful to describe the size and nature of the burden on a health-care system. These data help to guide public-health priorities, run studies of the causes of cancer and assess how effective certain prevention methods are. In 2019, more than one-third of countries didn’t have cancer registries, according to the World Health Organization (see ‘Counting the counters’; go.nature.com/31eupnn). And of those that have registries, only about half report high-quality data to the International Agency on Cancer Research (IARC). When it comes to ovarian cancer specifically, most countries don’t have the necessary data to inform policies, as stated by the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition, a non-profit organization working with groups of patients from around the globe. Source: WHO

The available data and incidence and mortality rates for ovarian cancer vary greatly from region to region (see ‘A global picture’). Northern Europe, eastern Europe and southeast Asia tend to see higher numbers of cases, whereas estimated age-standardized incidence rates in Latin America, East and South Asia and Africa are typically below the average. Source: WHO

However, countries with high incidence rates often ‘worked very hard to collect the data, as complete as they can,’ says Citadel Cabasag, who works on ovarian cancer surveillance for the IARC. Meanwhile, ‘there are some places where data is just not there,’ she says.It’s a predicament Mustapha is familiar with; she sees a clear gap between the official ovarian cancer statistics in Nigeria and the realities of her daily job. ‘Ovarian cancer was thought to be very rare in Africa,’ she says. ‘I don’t think it is true. Women die without having a diagnosis.’Whereas the United States, Australia and European countries typically have good-quality cancer registries, most others lag behind. As a result, a large number of cases are not counted, which makes it harder for scientists to understand the disease and its patterns. Epidemiologists find it challenging to pinpoint which populations are most affected, because it’s difficult to say whether higher rates of ovarian cancer can be attributed to differences in genetics or lifestyle, or are simply a sign of good counting.Search for answersSome of the best ovarian cancer registries can be found in northern and western European countries such as Denmark, Norway and Northern Ireland. Health authorities in these regions have been able to invest in the digital infrastructure and skilled work required to capture and analyse detailed cancer information from most of their populations, Cabasag says. Source: Queen’s Univ. Belfast

For example, these high-quality registries typically include data on the stages of the disease (see ‘Setting the stage’). This helps epidemiologists to understand whether ovarian cancer is detected early or late — a difference that has a considerable impact on prognosis. ‘If cancer has spread to other organs, then the treatment options are reduced,’ says Anna Gavin, founding director of the Northern Ireland Cancer Registry at Queen’s University Belfast, UK (see ‘The earlier the better’). ‘The outcomes are quite bad and survival very poor.’ (See ‘Deadly threat’.) Source: Queen’s Univ. Belfast

Data collection across Europe is typically well standardized. Mortality data in particular are recorded similarly in most countries, and allow for reliable cross-country comparisons to be made. ‘There are very clear rules. You can’t really go wrong,’ says Matteo Malvezzi, a statistician at the University of Milan, Italy. Incidence data, however, is harder to compare, given that even countries with good cancer registries might use different procedures and disease classifications, Cabasag says. Source: American Cancer Society

Partly as a result, many geographic patterns of ovarian cancer incidence are still ‘hard to explain’, Malvezzi says. It could be that rates are higher in central and eastern European countries than in many other European nations owing to the lower use of oral contraceptives1, for instance — the drugs are known to be protective against ovarian cancer2. But the data cannot provide a definitive explanation (see ‘Slow declines’). Source: SEER

In low- and middle-income countries, the quality of data collection makes drawing firm conclusions about the burden of ovarian cancer even more challenging. ‘When you look at Africa, all bets are off,’ says Malvezzi.Rates of ovarian cancer in Africa seem to be low, and researchers such as Mustapha are convinced that the official data are missing large swathes of people with cancer. However, even if that is true, it cannot be put down purely to how data are recorded. In unpublished work based on entries she was able to pull from her hospital’s ragged notebook, Mustapha found that over a three-year period, just 23% of the people who came through her hospital with scans that were highly suggestive of ovarian cancer had surgery to confirm the diagnosis. The majority of these people could not afford to pay for the procedure, so there’s little information on what happened to them.Look aheadOn the basis of available data, the IARC predicts that by 2040 the number of cases of ovarian cancer in Africa will rise by 87% — a greater increase than anywhere else in the world, driven by expected population growth (see ‘A building burden’). This will translate to higher costs for health-care systems, as more physicians, equipment and drugs are needed to treat ovarian cancer. ‘Even if countries don’t realize it’s a problem now, it is going to be an even bigger problem within 20 years,’ says Frances Reid, programme director at the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition. Source: IARC

To better enable the world to plan for the future, efforts are being made to improve ovarian cancer data collection worldwide. For example, the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition is working with the International Gynecologic Cancer Society on a large study that aims to gather information from more than 300 hospitals in 31 low- and middle-income countries — including Mustapha’s hospital in Zaria. It will document people’s experiences from diagnosis to treatment and beyond, and clarify how many people are affected by the disease. ‘We really want to be able to have a good evidence base from which local and national and international advocacy efforts can go forward,’ Reid says.Steps are also being taken to better standardize data collection practices globally. For instance, Gavin’s team in Belfast has developed a tool in collaboration with the IARC and others called CanStaging+, which is designed to help physicians in all parts of the world classify ovarian cancer by stage according to the same set of rules3. ‘We’re trying to harmonize the stage, so that when people say it’s stage four [cancer], it really is stage four,’ Gavin says.Mustapha thinks that this kind of standardization of data collection practices will lead to better cancer-control strategies and better outcomes for her patients. ‘We all need to work together with every stakeholder to see how we can improve this problem,’ she says. Nature 600, S48-S49 (2021)

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03719-5