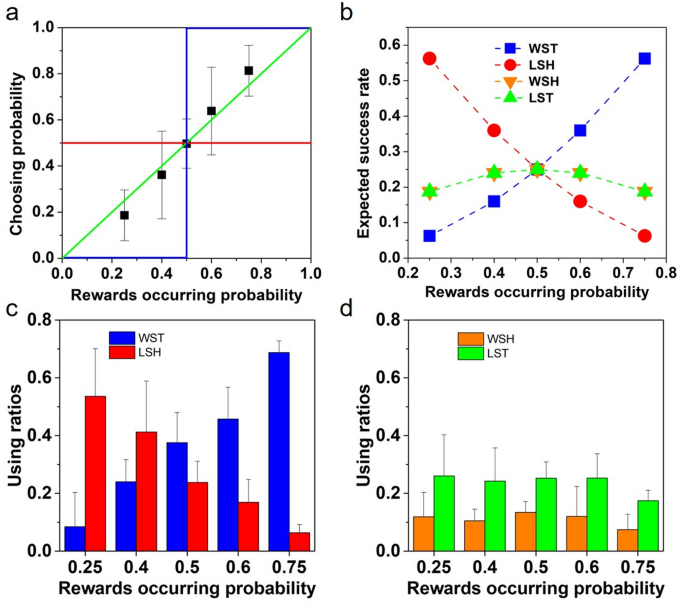

Switching costs in stochastic environments drive the emergence of matching behaviour in animal decision-making through the promotion of reward learning strategies A principle of choice in animal decision-making named probability matching (PM) has long been detected in animals, and can arise from different decision-making strategies. Little is known about how environmental stochasticity may influence the switching time of these different decision-making strategies. Here we address this problem using a combination of behavioral and theoretical approaches, and show, that although a simple Win-Stay-Loss-Shift (WSLS) strategy can generate PM in binary-choice tasks theoretically, budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates) actually apply a range of sub-tactics more often when they are expected to make more accurate decisions. Surprisingly, budgerigars did not get more rewards than would be predicted when adopting a WSLS strategy, and their decisions also exhibited PM. Instead, budgerigars followed a learning strategy based on reward history, which potentially benefits individuals indirectly from paying lower switching costs. Furthermore, our data suggest that more stochastic environments may promote reward learning through significantly less switching. We suggest that switching costs driven by the stochasticity of an environmental niche can potentially represent an important selection pressure associated with decision-making that may play a key role in driving the evolution of complex cognition in animals. In response to the uncertainty of natural environments, animals seem to be quite ‘smart’ in making decisions among various options by which they can accrue their fitness efficiently1,2. Although the fitness consequences of different decision-making strategies have been the focus of numerous studies, few have examined the animals’ responses to uncertainty and the conditions under which the adoption of or switch to a particular strategy become advantageous3.A general principle of choice in decision-making called probability matching (PM)4 has long been identified in animals, including humans5. PM occurs when decision-makers match their choice probabilities to a corresponding outcome probability (matching) rather than always choosing the outcome with the highest probability (maximizing)6,7. As a result, PM behavior is viewed by many as a ‘suboptimal’ or even an ‘irrational’ strategy8,9 because of the comparatively lower expected success rate than that of maximizing (see Supplementary Information 1). Some argue however, that adopting PM can be ‘ecologically rational’ if animals’ regularly encounter a situation in stochastic environments where PM is sufficient for reaching an immediate or short-term goal13. Helping to resolve this debate requires a combined theoretical and empirical assessment of why animals adopt non-maximizing behavior, but also identifying the conditions under which PM becomes beneficial in highly stochastic environments.Psychologists and economists have developed a range of theoretical models for modeling decision-making processes6,10,11. Win-Stay-Lose-Shift (WSLS) models have been extensively used to model behavior in decision-making tasks, especially from binary choice experiments12,13. In the most basic WSLS model, individuals repeat selections if they succeeded in getting rewards in the last trial (representing a ‘win’), but switch if they failed (a ‘loss’)13,14. PM can arise from a WSLS strategy when individuals initially search for patterns by repeat predictions but then change following failures9 (see Supplementary Information 1). Consequently, some view PM as simply a byproduct of a local decision-making process15 i.e. the outcome of a more complex search for patterns, rather than a strategy per se9. PM may also arise from reward (reinforcement) learning, when individuals respond according to an assessment of relatively long historical outcome information7. However, reward learning is cognitively more demanding than adopting a simple WSLS strategy, which has been labelled by some as a lazy cognitive shortcut16.Neither are these strategies mutually exclusive as animals may switch between alternative choices, or from one strategy to another. Switching may entail costs for decision-makers, arising primarily from economic considerations17. In nature, various switching costs also exist during animal decision making, including not only the energetic and temporal costs during switching18, but also costs such as increased predation risk19 or that of searching and assessing a new site to improve local familiarity20. Although a number of studies have considered such costs in decision-making, little is known about how environmental stochasticity may influence the switching time of different strategies, and then potentially drive the evolution of different decision-making strategies.Here we bridge those knowledge gaps, using a combination of behavioral experiments and simulation models to examine the use of PM behavior in animal decision-making from an adaptive viewpoint. We firstly use a series of binary choice experiments and theoretical models to investigate the decision-making behavior in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulates), and to determine the role of environmental variability (‘uncertainty’) in driving the use of two different decision-making strategies: WSLS and reward learning. Budgerigars are native to the arid interior habitats of Australia21, and are subject to significant spatial and temporal variation in food availability22, and consequently they face significant decision-making tasks while searching for rare and patchily distributed food and water sources. Thus, budgerigars are an appropriate species with which to conduct the experiments in this study. Additionally, in order to identify the conditions under which PM behavior can happen and to explore how the more complexed learning strategy would become profitable and adaptive, we construct simulation models based on the budgerigar experimental results.To test whether animals would really adopt a simple WSLS strategy and exhibit PM behavior, we conducted binary-choice experiments using budgerigars, which have been widely used in studies of different cognitive abilities, such as vocalization learning23,24, and problem solving25,26. In this study, eighteen unrelated budgerigars were used for the binary-choice experiments and their age ranged from under 1-year-old to 3 years old.Budgerigars were housed separately in different cages at a size of 20 × 20 × 20 cm prior to each experiment. Binary-choice experiments were conducted in a wire-meshed cage measuring 2 × 1 × 2 m (Supplementary Fig. S1). A single perch was positioned in the center of the cage at a height of 0.8 m from the ground. Two food cups were set on the front wall at a height of 1.6 m from the ground, separated by 1.6 m but only one cup contained the food reward in each trial. For illustration, we denote the side with a higher probability of having rewards as the H-side, and the other side as the L-side in the following. We assume the food rewards would occur on the H-side with a probability q, and on the L-side with a probability 1 − q.We first generated sequences of food reward locations for 100 trials under three different random levels (q = 0.5, 0.6 and 0.75) using MATLAB (version 7.5, R2007b, The MathWorks Inc.). Each bird was placed in the experimental cage for two days to adapt to the environment, and foraged on food provisioned in the cups in prior (both cups contain foods during this period). Before the experiments, each bird was food deprived for 24 h. Following this, for each experimental trial, we placed approximately 20 grains of millet in the food cup. Once a bird had made a decision and had eaten some millet (after ~ 8–10 s), we removed both food cups, after which the bird would fly back to the perch and wait for the next trial, which was conducted after a period of one minute. If the bird chose a wrong side (i.e., without food rewarding), we would allow it to fly to the other side, after which we immediately removed both food cups from the cage. Since the study subject would become satiated following approximately 30 trails, the total of 100 trials were subsequently conducted over three consecutive days. On each day after conducting the experiments, the bird would be food deprived until the experiments resumed on the following day. To avoid memory interference between random levels, we assigned each bird to only one set of 100 trials. We used three different birds for the experiments under each of the random levels of (q=0.6) and 0.75, and five birds under the random level of (q=0.5). To avoid possible effects of side preference, we also used another three different birds for the experiments under each of the random levels of (q=0.6) and 0.75, and one bird under the random level of (q=0.5) with the same sequences of food locations, but changing the position of food reward to the opposite side in each trial.This study complies with all applicable governmental regulations concerning the ethical treatment of animals. All animal use and care was done in compliance with the guidelines of Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). This work was permitted by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Zoology, CAS.Assessing the outcome information for decision-makingTo assess how our budgerigars made their decisions through reward learning, we firstly used a one-parameter (time constants (tau )) leaky integration model to quantify the outcome information in each trial27. This model uses a function similar to an exponential filter, which has been derived from a signal processing method28. Since food reward was the only income earned by budgerigars during the binary choice experiments, we integrated the reward history of each side as the outcome information. Due to memory capacity limitation29 only a finite number of past trials might be informative to decision-makers. Specifically, the outcome information of each side (({y}_{i}={y}_{H}) for the H-side or ({y}_{L}) for the L-side) in trial (t) was calculated as:({y}_{i}(t) = (1-a){y}_{i}(t-1)+a{x}_{i}(t-1)) or rewritten as$${y}_{i}left(tright)=asum_{k=2}^{t}{x}_{i}left(k-1right){left(1-aright)}^{t-k},$$where ({x}_{i}(t-1)) is the income earned in the last one trial (1 or 0), and (a=1-expleft(-1/tau right)) is a constant between 0 and 1, where (tau ) is the time constant. We can see that the more recent reward is more informative for making the current decision (Supplementary Fig. S2). Moreover, the reward information from the past (tau ) trial(s) can explain 63.2% of the output ({y}_{i}(t)), and the past (3tau ) and (4tau ) trials can explain 95% and 98.2% of the output value, respectively.Reward learning strategy assessmentTo explore how budgerigars made decisions according to the outcome information integrated using different time constants (tau ), we constructed several generalized linear mixed-effect models (GLMMs) with binomial error (and logit link function) under different time constants (tau ). In each model, we set the selected side (1 for H-side, and 0 for L-side) in each trial as the dependent variable. The difference in outcome information between the two sides ((Delta yleft(t, tau right)={y}_{H}left(t, tau right)-{y}_{L}left(t, tau right))) and the random level that individuals encountered (i.e., q = 0.5, 0.6 or 0.75) were used as the independent variables in each model. Individual ID was set as a random effect. Normally, as our budgerigars had no prior information to identify different random levels, we would expect random level to be an insignificant factor in the model. Hence, we subsequently assessed the significance of random level in different GLMMs using likelihood ratio tests (LRT) using R function anova. The two models used here are shown by the following,Model 1: Selected side ~ (Delta yleft(t, tau right)) + random level + (1|ID),Model 2: Selected side ~ (Delta yleft(t, tau right)) + (1|ID).All models were compared using Akaike’s information criterion, AIC30, to identify the best-fit time constant in modeling budgerigars’ decisions. Note that we had conducted exploratory analyses by including the side effect (set as 1 or 2 to indicate the experiments conducted under the same sequences with opposite food locations) as another independent variable, which showed that our budgerigars did not have certain side preference during decision-making (see Supplementary Table S1). Hence, the side effect was not considered for further analysis. We had also constructed another three outcome information processing models to assess the decision making of our budgerigars; 1: memory without decay; 2: memory without decay and losing represents a negative income; 3: memory with decay and losing represents a negative income. All of these models showed much higher AIC values than the model described above (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). All GLMMs were implemented using function glmer in the lme4 package31 in R v.3.5.032.Simulations of the best-fit statistical modelTo determine the robustness of our experimental results and explore how environmental stochasticity influences switching time between decision-making strategies, we conducted computer simulations under different random levels ((q) ranged from 0.50 to 0.85, stepped by 0.05) to assess the behavior of the deduced reward learning strategy (i.e., the best-fit regression model, see Supplementary Fig. S3); specifically, the choosing probability of the H-side would be predicted using the statistical model in each trial.For each simulation, we first deduced a reward learning strategy from the best-fit regression model (Supplementary Fig. S3). To capture the uncertainty, we assumed a multivariate normal distribution for regression coefficients. We generated the coefficients of a model of reward learning strategy usi

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-02979-5

Switching costs in stochastic environments drive the emergence of matching behaviour in animal decision-making through the promotion of reward learning strategies