1.Moran, D. et al. Carbon footprints of 13 000 cities. Environ Res Lett 13, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aac72a (2018).2.Gurney, K. R. et al. Comparison of Global Downscaled Versus Bottom-Up Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions at the Urban Scale in Four US Urban Areas. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres 124, 2823–2840, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018jd028859 (2019).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 3.Bin, S. & Dowlatabadi, H. Consumer lifestyle approach to US energy use and the related CO2 emissions. Energy Policy 33, 197–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-4215(03)00210-6 (2005).Article Google Scholar 4.Lee, S. & Lee, B. J. E. P. The influence of urban form on GHG emissions in the US household sector. 68, 534–549 (2014).5.Wiedenhofer, D. et al. Unequal household carbon footprints in China. Nature Climate Change 7, 75 (2017).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 6.Ding, Q., Cai, W., Wang, C. & Sanwal, M. The relationships between household consumption activities and energy consumption in china— An input-output analysis from the lifestyle perspective. Applied Energy 207, 520–532, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.06.003 (2017).Article Google Scholar 7.Zhang, Y.-J., Bian, X.-J., Tan, W. & Song, J. The indirect energy consumption and CO2 emission caused by household consumption in China: an analysis based on the input–output method. Journal of Cleaner Production, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.044 (2015).8.Wang, Z., Liu, W. & Yin, J. Driving forces of indirect carbon emissions from household consumption in China: an input–output decomposition analysis. Natural Hazards 75, 257–272, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1114-7 (2014).Article Google Scholar 9.Liu, H.-T., Guo, J.-E., Qian, D. & Xi, Y.-M. Comprehensive evaluation of household indirect energy consumption and impacts of alternative energy policies in China by input–output analysis. Energy Policy 37, 3194–3204, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.04.016 (2009).Article Google Scholar 10.Long, Y., Yoshida, Y., Zhang, R., Sun, L. & Dou, Y. Policy implications from revealing consumption-based carbon footprint of major economic sectors in Japan. Energy Policy 119, 339–348, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.052 (2018).Article Google Scholar 11.Shigetomi, Y., Nansai, K., Kagawa, S. & Tohno, S. Changes in the carbon footprint of Japanese households in an aging society. Environmental science & technology 48, 6069–6080, https://doi.org/10.1021/es404939d (2014).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 12.Feng, K. & Hubacek, K. Carbon implications of China’s urbanization. Energy, Ecology and Environment 1, 39–44, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40974-016-0015-x (2016).Article Google Scholar 13.Kanemoto, K., Shigetomi, Y., Hoang, N. T., Okuoka, K. & Moran, D. Spatial variation in household consumption-based carbon emission inventories for 1200 Japanese cities. Environmental Research Letters 15, 114053, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc045 (2020).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 14.UNFCCC. Submission of Japan’s Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC)-Japan. (2015).15.Chen, G. W. et al. Review on City-Level Carbon Accounting. Environmental science & technology 53, 5545–5558, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b07071 (2019).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 16.Oda, T., Maksyutov, S. & Andres, R. J. The Open-source Data Inventory for Anthropogenic CO2, version 2016 (ODIAC2016): a global monthly fossil fuel CO2 gridded emissions data product for tracer transport simulations and surface flux inversions. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 10, 87–107, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-87-2018 (2018).ADS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 17.Crippa, M. et al. High resolution temporal profiles in the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. Scientific Data 7, 121, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0462-2 (2020).Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 18.Sargent, M. et al. Anthropogenic and biogenic CO2 fluxes in the Boston urban region. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 7491–7496, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1803715115 (2018).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 19.Moore, J. & Jacobson, A. D. Seasonally varying contributions to urban CO2 in the Chicago, Illinois, USA region: Insights from a high-resolution CO2 concentration and delta C-13 record. Elementa-Science of the Anthropocene 3, https://doi.org/10.12952/journal.elementa.000052 (2015).20.Murakami, K., Kaneko, S., Dhakal, S. & Sharifi, A. Changes in per capita CO2 emissions of six large Japanese cities between 1980 and 2000: An analysis using ‘The Four System Boundaries’ approach. Sustainable Cities and Society 52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101784 (2020).21.Mi, Z. F. et al. Consumption-based emission accounting for Chinese cities. Appl Energ 184, 1073–1081, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.06.094 (2016).Article Google Scholar 22.Nangini, C. et al. A global dataset of CO2 emissions and ancillary data related to emissions for 343 cities. Scientific Data 6, 180280, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.280 (2019).CAS Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar 23.Gurney, K. R. et al. Under-reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in US cities. 12, 1–7 (2021).24.Lee, J., Taherzadeh, O. & Kanemoto, K. The scale and drivers of carbon footprints in households, cities and regions across India. Global Environmental Change 66, 102205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102205 (2021).Article Google Scholar 25.Shigetomi, Y. et al. Driving forces underlying sub-national carbon dioxide emissions within the household sector and implications for the Paris Agreement targets in Japan. Applied Energy 228, 2321–2332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.07.057 (2018).Article Google Scholar 26.Golley, J. & Meng, X. Income inequality and carbon dioxide emissions: The case of Chinese urban households. Energy Economics 34, 1864–1872, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2012.07.025 (2012).Article Google Scholar 27.Girod, B. & De Haan, P. More or better? A model for changes in household greenhouse gas emissions due to higher income. Journal of Industrial Ecology 14, 31–49 (2010).CAS Article Google Scholar 28.Van Vuuren, D. P. et al. Comparison of top-down and bottom-up estimates of sectoral and regional greenhouse gas emission reduction potentials. 37, 5125–5139 (2009).29.Pachauri, S. & Spreng, D. Direct and indirect energy requirements of households in India. Energy policy 30, 511–523 (2002).Article Google Scholar 30.Shigetomi, Y., Nansai, K., Kagawa, S. & Tohno, S. Fertility-rate recovery and double-income policies require solving the carbon gap under the Paris Agreement. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 133, 385–394, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.11.017 (2018).Article Google Scholar 31.Huang, Y., Shigetomi, Y., Chapman, A. & Matsumoto, K. I. J. E. Uncovering household carbon footprint drivers in an aging, shrinking society. 12, 3745 (2019).32.Yin, L. Japan regional carbon emissions shift after electricity allocation. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14472534.v1 (2021).33.Jiang, Y., Long, Y., Liu, Q., Dowaki, K. & Ihara, T. Carbon emission quantification and decarbonization policy exploration for the household sector – Evidence from 51 Japanese cities. Energy Policy 140, 111438, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111438 (2020).CAS Article Google Scholar 34.Mi, Z. et al. Carbon emissions of cities from a consumption-based perspective. Applied Energy 235, 509–518, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.10.137 (2019).Article Google Scholar 35.Shen, L. et al. What drives the carbon emission in the Chinese cities?—A case of pilot low carbon city of Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production 174, 343–354, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.333 (2018).Article Google Scholar 36.Xia, Y. et al. Assessment of the economic impacts of heat waves: A case study of Nanjing, China. Journal of Cleaner Production 171, 811–819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.069 (2018).Article Google Scholar 37.Long, Y. & Yoshida, Y. Quantifying city-scale emission responsibility based on input-output analysis – Insight from Tokyo, Japan. Applied Energy 218, 349–360, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.02.167 (2018).Article Google Scholar 38.Moran, D. et al. Carbon footprints of 13 000 cities. 13, 064041 (2018).39.Kanemoto, K., Shigetomi, Y., Hoang, N. T., Okuoka, K. & Moran, D. J. E. R. L. Spatial variation in household consumption-based carbon emission inventories for 1,200 Japanese cities. (2020).40.Jorgenson, A., Schor, J. & Huang, X. Income Inequality and Carbon Emissions in the United States: A State-level Analysis, 1997–2012. Ecological Economics 134, 40–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.12.016 (2017).Article Google Scholar 41.Bai, Y., Zheng, H., Shan, Y., Meng, J. & Li, Y. J. E. s. F. The consumption‐based carbon emissions in the Jing‐Jin‐Ji urban agglomeration over China’s economic transition. e2021EF002132.42.FIES. Family Income and Expenditure Survey. Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan.43.Nansai, K. et al. Estimates of embodied global energy and air-emission intensities of Japanese products for building a Japanese input-output life cycle assessment database with a global system boundary. Environmental science & technology 46, 9146–9154, https://doi.org/10.1021/es2043257 (2012).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 44.Nansai, K. et al. Improving the Completeness of Product Carbon Footprints Using a Global Link Input–Output Model: The Case of Japan. Economic Systems Research 21, 267–290, https://doi.org/10.1080/09535310903541587 (2009).Article Google Scholar 45.Nansai, K. et al. Carbon footprint of Japanese health care services from 2011 to 2015. 152, 104525 (2020).46.Nansai, K. Embodied energy and emission intensity data for Japan using input–output tables (3EID). National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan, http://www.cger.nies.go.jp/publications/report/d031/index.html (2019).47.Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, J. Oil product price. https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/statistics/petroleum_and_lpgas/pl007/results.html.48.Agency of Natural Resource and Energy, J. Japan Energy White Book 2018 (2018).49.Oil Information Center, t. I. o. E. E., Japan LP Gas price. https://oil-info.ieej.or.jp/price/price.html.50.Oil Information Center, t. I. o. E. E., Japan LPG consumption survey of Japan. https://oil-info.ieej.or.jp/documents/data/20080303_2.pdf (2006).51.Statistics, J. G. Retail price survey. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200571&tstat=000000680001&cycle=7&year=20140&month=0&result_back=1&cycle_facet=cycle&tclass1val=0.52.Statistics, J. G. Consumer Price Index. https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200573&tstat=000001044944&cycle=7&year=20150&tclass1=000001044990&cycle_facet=cycle (2015).53.MOE. Greenhouse Gas emission intensity, Ministry of Environment, Japan. https://ghg-santeikohyo.env.go.jp/calc.54.MOE. A guide of checking greenhouse gas emissions, Ministry of Environment, Japan. https://www.env.go.jp/press/files/jp/21329.pdf (2013).55.Lenzen, M. Primary energy and greenhouse gases embodied in Australian final consumption: an input–output analysis. Energy policy 26, 495–506 (1998).Article Google Scholar 56.Lenzen, M., Murray, S. A., Korte, B. & Dey, C. J. Environmental impact assessment including indirect effects—a case study using input–output analysis. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 23, 263–282, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0195-9255(02)00104-x (2003).Article Google Scholar 57.Lenzen, M. et al. A comparative multivariate analysis of household energy requirements in Australia, Brazil, Denmark, India and Japan. Energy 31, 181–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2005.01.009 (2006).Article Google Scholar 58.Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Turner, K. & Barrett, J. Examining the global environmental impact of regional consumption activities—Part 2: Review of input–output models for the assessment of environmental impacts embodied in trade. Ecological economics 61, 15–26 (2007).Article Google Scholar 59.Kanemoto, K., Lenzen, M., Peters, G. P., Moran, D. D. & Geschke, A. Frameworks for Comparing Emissions Associated with Production, Consumption, And International Trade. Environmental science & technology 46, 172–179, https://doi.org/10.1021/es202239t (2012).ADS CAS Article Google Scholar 60.Long, Y., Dong, L., Yoshida, Y. & Li, Z. Evaluation of energy-related household carbon footprints in metropolitan areas of Japan. Ecological Modelling 377, 16–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2018.03.008 (2018).Article Google Scholar 61.Kawajiri, K., Ihara, T., Hatayama, H. & Tahara, K. Revealing hidden CO2 impacts from consequential consumption by matrix analysis: Application to Japanese single households. Journal of Cleaner Production 172, 582–590 (2018).CAS Article Google Scholar 62.NIPSSR. Household Projections for Japan 2010-2035:Outline of Results and Methods National Institute of Population and Social Security Research of Japan (2014).63.NSFIE, M. National Survey of Family Income and Expenditure. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/zensho/.64.Koide, R. et al. Carbon footprints and consumer lifestyles: an analysis of lifes

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-021-01086-4

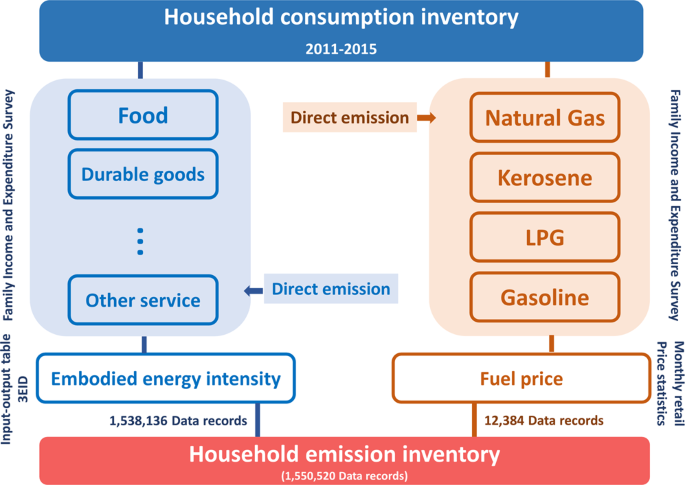

Monthly direct and indirect greenhouse gases emissions from household consumption in the major Japanese cities