This research aimed to study the genetic diversity of the Iberian B. terrestris populations under threat of introgression from managed non-native populations at both the spatial and temporal scales. Our results, based on extensive sampling throughout the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal), indicate that the mitochondrial haplotype associated with central European populations of B. terrestris has expanded beyond both the natural intergradation area (i.e., the Pyrenees) and the anthropic one (i.e., the southeast region), reaching most of the north–south gradient with some exceptions in the northwest. These results contrast with the haplotype distribution in historical populations (i.e., REF_SP80, specimens collected in Spain 40 years ago) in which all individuals presented the Iberian haplotype, except one individual detected close to the natural intergradation area in the Pyrenees, where natural hybridization occurs. These results support the idea that the endemic Iberian haplotype was predominant in the territory and that, due to hybridization and introgression events with naturalized commercial breeds, the central European haplotype has recently spread into the environment. This change in the haplotype distribution of the peninsula is a first signal of how this expansion is modifying the genetic pool of the populations, which may soon develop into losses of local adaptation6,45. Another hypothesis to explain the present genetic structure could be migration, although unlikely. In the context of climate change, the only plausible hypothesis is a migration from the Southern area to the north1. However, based on our knowledge, the European subspecies was never recorded in the Southern region of Spain and we did not detect any individuals with the central European haplotype in the historical data set but one, close to the natural intergradation area in Pyrenees.

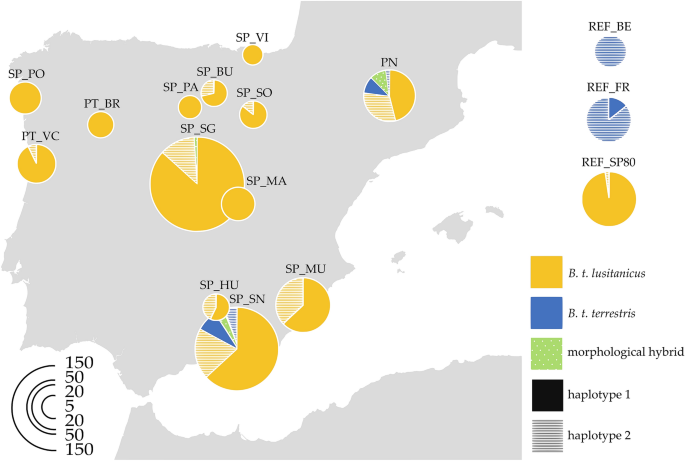

Our results expand the current knowledge about the genetic integrity of B. t. lusitanicus in the Iberian Peninsula. Previous records of B. t. terrestris and hybrid individuals have occurred only in the south23,25,39 and west24 (putative genetic hybrids) of the Iberian Peninsula, whereas we have found evidence of introgression in most of the territory (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). The presence of the central European haplotype in the central area of the peninsula, where the subspecies B. t. terrestris has not been detected, could be due to the dispersion of individuals from areas where commercial breeds are being used (greenhouses in the region or an expansion from the south), as B. terrestris dispersion can be assisted by strong winds to cross long distances15,33. On the other hand, in the most northwestern localities sampled (SP_PO, SP_BR and SP_PA), the central European haplotype was not found, which suggests that these populations of B. t. lusitanicus are less affected by introgression, probably due to a lower density of greenhouses in the area, as well as a larger distance from the two main areas of intergradation40 (Supplementary Fig. S1 Online).

This study confirms that the inclusion of samples from old collections is crucial to assess the evolution of the genetic diversity of local populations, as has been done before in other species of the genus Bombus (Latreille, 1802)29. Furthermore, the use of old samples as historical references in population genetics will be especially important in subsequent years, as we monitor the expected changes in the distribution of not only B. terrestris subspecies but also other organisms that are affected by climatic change and anthropisation. The distribution range of B. t. lusitanicus, instead of shifting or reducing, is expanding, both in altitude and latitude13,18,46, while the populations of B. t. audax in the UK have become bivoltine7. Given the subspecies’ similar resistance to heat stress14, further changes due to climatic change are expected to occur. Even under these conditions, although we must assume that hybridization may play a key role in evolution47,48, there is a consensus that human-induced introgression of non‐indigenous organisms harms native gene pools45,49,50.

As previous studies on the genetic diversity of the species have reported, the heterozygosity values obtained in this analysis, the assignment test (GeneClass) and the clusters inferred (Structure and DAPC) suggest an intense gene flow among B. terrestris populations, which leads to a reduced population structure in a continuum that is not only peninsular but also continental33,51,52. When comparing the Iberian populations with their historical reference, only slight variations can be observed in the allelic frequencies, although the data show an overall decrease in allelic richness and expected heterozygosity values. Conversely, the Wilcoxon test suggests that hybridization and introgression events are affecting the native populations by increasing the genetic diversity of those populations with hybrid individuals, which is expected from the admixture of different gene pools45. Given the low structure of bumblebee populations, the effect of this change is difficult to measure, but if this dynamic continues, the loss of endemicity and increased homogenization of European populations will be recurring concerns in the future.

The analysis of genetic diversity in the Iberian Peninsula showed the lowest values in the central peninsular populations (Sierra de Guadarrama: SP_SG2, SP_SG3), where the highest number of diploid males and one triploid male were found. These results could represent a sign of a potential threat of inbreeding depression in the populations35, although it has been previously discussed that B. terrestris is able to withstand inbreeding in its populations56. In this sense, B. terrestris does not show mating preferences between related and unrelated individuals35, so there are no mechanisms preventing diploidy or even triploidy in males53. However, these results should be taken into account in future studies on the species, as the ploidy values obtained in this study were higher than those of populations of endangered species such as B. florilegus Panfilov, 1956 (2.7%)54 or B. muscorum Linnaeus, 1758 (5%)55.

Given that B. terrestris can escape from greenhouses23,24 and the great expansion capacity of the managed populations in the environment15, we emphasize the importance of the propagation of the commercial B. terrestris subspecies from greenhouses across the Iberian Peninsula as a driver of population change. Moreover, the inadequate management of colonies by breeding companies and farmers after colony use due to a lack of information about the consequences of their dispersal in the environment is another little-addressed factor contributing to the emergence and dispersion of commercial breeds (implied by the presence of the central European haplotype) in the environment. Some of the mispractices that occur in the territory include the outdoor use of colonies, incomplete removal or abandonment of colonies24 and attempts to manage the nesting of commercial queens in the environment (personal observation). To avoid escapes, bumblebee nests should be placed only inside greenhouses and destroyed at the end of the crop pollination campaign before new sexual individuals emerge. The arrival of commercial breeds of B. terrestris into new environments and their subsequent colonization is guaranteed unless stricter regulations on their transport and management are adopted16, both outside and within the species’ natural distribution range8,13. To our concern, there is still no legislation regarding the management of bumblebee colonies for agricultural use in the Iberian Peninsula beyond the advice and instructions of the provider companies. Because the Iberian Peninsula is a large producer and exporter of fruits and vegetables, and therefore an intensive user of commercial pollination services, we endorse stricter legislation on the importation of foreign subspecies and support for companies breeding local subspecies11, as the breeding of B. t. lusitanicus does not involve additional costs compared with other subspecies of B. terrestris (de Jonghe; Rasmont; personal communication). Such regulations are already in effect in other regions within the natural distribution range of the species, such as the United Kingdom, Norway and the Canary Islands. Authorization of the importation of exotic taxa should only be legalised after studying the survival rate, expansion capacity and environmental impact of the managed populations. It is important to coordinate an update of the existing legislation with more active dissemination to first-hand users on the correct management of commercial breeds and the benefits of using local subspecies.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-01778-2